Image

The deck of the Energy Atlantic is a maze of pipes and metal that help carry and contain natural gas products to Port Arthur, Texas, on Jan. 12, 2016. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Dustin R. Williams)

by John Moritz, Rhode Island Current

September 15, 2025

At first glance, the route of one of America’s most controversial pipeline projects might not seem to have much to do with New England.

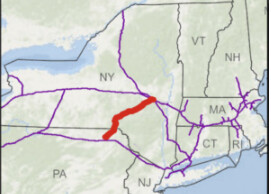

The proposed 125-mile pipeline between Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale field and upstate New York, however, is part of a long-standing effort to increase the flow of natural gas into parts of Connecticut and, by extension, the neighboring states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island and New Hampshire.

Such efforts have recently drawn interest from a politically-diverse group of figures such as Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont as well as Republican President Donald J. Trump and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, all of whom view natural gas as a way of reducing the region’s cost-of-energy burden.

Opponents, meanwhile, argue that building a new pipeline will only worsen pollution and the release of climate-altering greenhouse gases, while doing little to bring down prices.

The Constitution Pipeline is being developed by Williams Companies, a large operator of pipelines across the United States. The pipeline would have the ability to carry up to 650 million cubic feet of gas a day, according to the company, enough to serve about 3 million homes.

Williams first received federal approvals to build the pipeline more than a decade ago, but the project hit a snag when the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation declined to issue a water quality permit in 2016.

The project continued to languish until the developers resubmitted applications to state and federal regulators earlier this year.

“Williams remains committed to advancing the Constitution Pipeline project and has submitted permit applications,” to regulators in New York and Pennsylvania, the company said in a statement this month. “We are also continuing to work with the states, Congress, and the Administration to strengthen U.S. energy markets, lower costs for American families, and support long-term economic growth.”

Pending those approvals, Williams estimates that the pipeline should begin construction next year and enter service near the end of 2027.

While the Constitution Pipeline itself will not carry gas into Connecticut, its terminus in New York will link up with two existing pipelines — the Tennessee and Iroquois systems — that serve both the state and the wider region.

Those pipelines already operate at or near capacity, officials say, creating a supply bottleneck particularly during winter months when gas is used to both heat homes and fuel the power plants that produce the bulk of the region’s electricity.

In order to reduce that bottleneck, pipeline operators in Connecticut are pursuing their own expansion projects.

Iroquois pipeline’s owners, for example, are seeking to build a series of compressors that would push an additional 125 million cubic feet of gas through the each day, an increase of 8.3% over its existing capacity. Meanwhile, Canadian energy company Enbridge has its own plans to expand its regional pipeline, the Algonquin, by 2029.

Carolina Kulbeth, a spokesperson for Tennessee Pipeline operator Kinder Morgan, said in a statement that expanding pipeline capacity is “critical” to eliminating existing constraints on gas supply.

“New pipeline infrastructure is the only way to ensure reliability and affordability in the New England region, as demand continues to rise among residential, commercial, and industrial customers,” Kulbeth said.

Trump himself has touted the pipeline’s benefits, saying that it would lower energy prices by up to $5,000 per family in the Northeast — figures that critics say are wildly inflated.

“I can tell you Connecticut wants it and all of New England wants it,” Trump said in March. “And who wouldn’t it?”

In May, the Wall Street Journal reported that the resurrection of the Constitution Pipeline was linked to negotiations between the Trump administration and New York over the fate of another project, Empire Wind.

Federal authorities had pulled permits for the wind project in April, only to reverse course around the same time that Williams resubmitted its pipeline applications.

While New York Gov. Kathy Hochul has denied making any explicit promises to approve the pipeline, she has expressed a willingness to work with the administration and developers on unnamed “new energy projects” that comply with state law.

Lamont, however, has strongly suggested that the two projects are intertwined.

After the Trump administration last week ordered a halt in construction on another wind project being staged in New London, Lamont expressed surprise at the decision given his prior support for the development of new pipelines.

“We’re already having very productive conversations with Williams pipeline company and [the secretaries] of Energy and Interior regarding how we can get additional sources of power here to this region, including American natural gas,” Lamont said. “So I don’t think there’s a conflict there.”

Critics of pipeline expansion argue that projects such as Constitution are at odds with the commitments made by local elected officials to slowly wean the region off of its reliance on fossil fuels. Connecticut, for example, has laws pledging to get all of the state’s power needs from carbon-free sources no later than 2040 and achieving economy-wide net-zero emissions 10 years after that.

In addition, they point to the region’s already sky-high energy prices to argue that importing more natural gas is not an effective solution.

“This is not about what’s better for the climate, or air or energy costs,” said Samantha Dynowski, the Connecticut state director for the Sierra Club. “This is about, you know, Trump’s buddies, his fossil fuel buddies.”

During his presidential campaign last year, Trump pledged to ease environmental restrictions and approve new drilling, pipeline and other fossil fuel projects. At the same time, he attempted to solicit $1 billion in campaign donations from the oil and gas industry.

Pipeline projects such as the Iroquois and Algonquin expansion projects have also faced local opposition in Connecticut, particularly in Brookfield where residents have complained about plans to build a new compressor station in close proximity to a middle school.

The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection announced its tentative approval of the compressor on July 31.

This article first appeared on CT Mirror and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Rhode Island Current is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Rhode Island Current maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Janine L. Weisman for questions: info@rhodeislandcurrent.com.

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.