Image

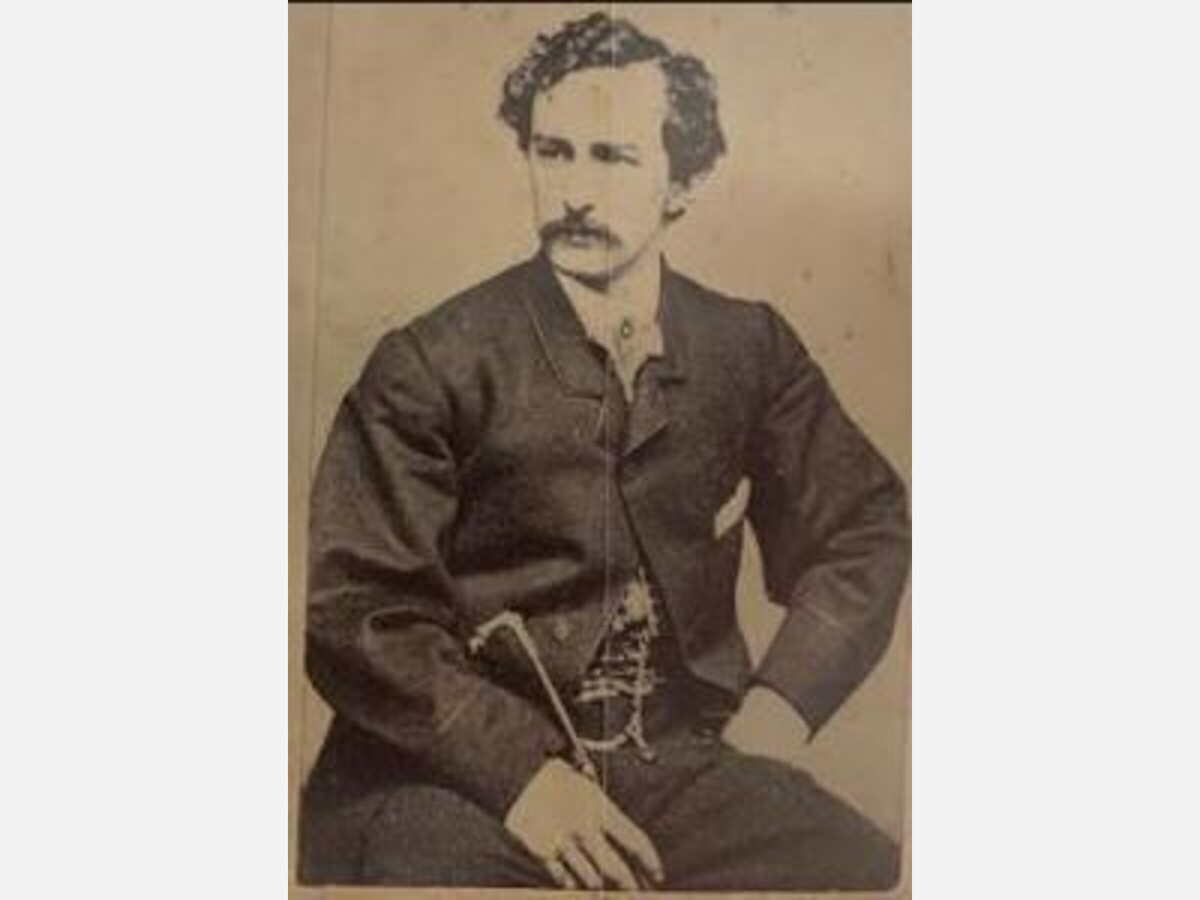

[April 15 being the anniversary of the nation's first presidential assassination (and tomorrow the anniversary of the 'first emancipation proclamation' -- see bottom of story for more), Jim Johnston has kindly shared a great and little known story about the Lincolns and Booths -- and much else of 19th century America.] (Image above from Mr. Johnston's collection)

By James C. Johnston Jr.

In April of 1865, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate States Southern Sympathizer, and noted actor, John Wilkes Booth. Booth was in his mid-twenties as were the assassins of Presidents McKinley and Kennedy and the would-be assassin of President Ronald Reagan generations later, and like those assassins, Booth harbored private grievances and felt artistically underappreciated even though he was a nationally acclaimed actor from a very large and distinguished family of well-established thespians which had been led by his monumentally talented father Junius Brutus Booth.

The life of an actor was a hard one which demanded much in terms of travel and separation from one’s loved ones. Travel was hard in those far-away times. By the 1840s and 1850s, railroading was still a coming thing. Most cities, where more sophisticated audiences could be found, were located on the sea coast or great rivers which had better access by ship. The Great Junius Brutus Booth ranged from London to New York, to Boston, to Atlanta, to New Orleans, and even to San Francisco in the “Gold Rush” Period in order to dazzle his audiences with the brilliance of his acting. People anticipated his arrival in their cities with bated breath. A night with Booth on the stage was a guaranteed night to remember forever.

Alas as time went on in Booth’s career, the older Booth was frequently drunk which was seen as a failure of his son, Edwin Booth, who traveled with his father from his childhood onward specifically charged with the job of keeping his father sober. Many a night, the teen-aged Edwin Booth went on in his drunken father’s place playing Macbeth in “The Scottish Play”, or Romeo, or Hamlet Prince of Denmark. All the Booth children knew the great plays by heart from childhood. Learning and playing these great classics was the very “Stuff” of their childhoods, because they were all destined for the stage. After all, that is where the Booths lived.

It was to the metropolitan areas of the new American Republic that actors flocked to find work just as actors do today, and there was nothing that the New Americans loved so well in their theatres as “The Well-Made-Play.” The works of the great old masters like Shakespeare and Ben Johnson were forever popular as were the melodramas and comedies typified by one of Abraham Lincoln’s perennial favorites, Our American Cousin, which the great Laura Keene eventually made her own as a theatrical vehicle in which to show off her brilliance on the stage. But it was “The Well Made Play” that would hold the imagination and attention of theater-goers during a large part of the 1800-1870 Period in American Theater.

“The Well-Made-Play” was introduced to the American Stage in the early part of the 19th Century. “The Well Made Play” was a well-known theatrical art form in Europe from 1766 onward, but its journey beyond the precincts of America’s coastal theatrical venues took some time. The movement of the great new American Nation of the United States in its march West had been fairly fast, but at the same time, it had followed its own deliberate pace. For example, the village of Fort Pitt of 1833 would take a little while to evolve into Chicago by the Civil War Period and make room for a home for serious theatre.

The projected persona of the actors of that time was also essential to an audiences’ understanding of the action on the stage. In an age before microphones, it was essential that actors be both heard and understood clearly by those sitting in every part of “The House”. This led to the use of an Over-the-Top style of acting that was very emotional, loud, deeply resonate, overly dramatic, and featured grand physical gestures that could be easily seen and understood by the people sitting at the back of the theater itself. Altogether, this very exotic entertainment provided those who attended the theatre with an “Experience of a lifetime”. I suppose attending the theater in those long-ago days was sort of like going a rock concert! I know from my personal experience of doing college Repertory Theater in the 1960’s that it was a great point of pride to the college company that we never used microphones. Our voices were made to effortlessly fill the house. Later on I would find this to be a great asset in the classroom and in the lecture hall.

It is no secret that the Victorians still embraced an appreciation of the formula of “The Well-Made-Play” which first had marked the 18th century dramas of Eugene Scribe and August von Kotzebue who had invented that great theatrical device in his play, The Stranger. Scribe’s and Kotzebue’s formula consisted of: a tight plot, well defined characters, who are led into dramatic situations by both fate and the manipulations of evil-doers, and who are also frequently un-done by a lack of crucial information which could have been provided by letters and other written clues and sources of information which always seemed to have been at-hand or hidden or placed somewhere on the stage itself!

For the unsophisticated American audience of the 19th Century, the situation was often so fraught with excitement and tension that some theater-goers could not tolerate the pressure. Some members of the audience got so caught-up in the action of the play that they began calling out to their acting favorites on the stage alerting them and warning them about “the secrets” which were being kept from them or perhaps the fact that the villain of the piece was hiding in the closet listening to every word they spoke.

Sometimes the actor would use this emotional involvement of the audience to heighten the sense of dramatic tension by cupping his hand to his ear as if he had become aware of a distant voice of warning but could not quite make out what message was that was being yelled out to him! I am sure that you can imagine the utter frustration of the poor audience members caught-up in the realism of the moment as they were being forcibly removed from their seats and hustled out of the theater by the ushers, with arms flailing and voice screaming, “He’s in the closet, and he’s got a gun!”

There were more than a few English and American acting dynasties that did develop in the craft of “Treading the Boards” that achieved great international fame! This grand theatrical tradition was something in which the children of great acting families, who were the natural heirs to the grease-paint and roars of the crowd, grew into. Theaters were their universities, and their thespian parents were their professors. Their curriculum was provided in the works of Shakespeare, Ben Johnson, Addison and Steele, and the other popular and classic playwrights of the era as well as the tried and true theatrical authors of material of the past. The Great Anglo-American Acting families like: The Kembles, The Drews, the Barrymores, The Irvings, and The Booths were among those most popular in that early to late Great Victorian Period. Indeed, they dominated the English speaking stages on both sides of the Atlantic for most of the century.

By the 1860’s, Junius Booth Jr., Asia Booth, John Wilkes Booth, and other members of that illustrious Booth Family dominated the theatrical stages of the American Nation, but none were as acclaimed as much as Edwin Booth who was considered to be America’s finest actor and later founder of New York’s famed Player’s Club. Youngest brother, teen-aged John Wilkes Booth, was always very jealous of his older brother, Edwin, who dominated the New York stage and enjoyed the adulation of the sophisticated venues of the more cosmopolitan theater-going North.

John Wilkes Booth was very popular in theaters of the South who admired the brash swagger of the youngest member of the family who bestrode their stages with skill and, shall we say, less subtle demonstrations of his dramatic art. Even during the days of the Civil War, theatrical engagements both North and South were contracted with well-known Northern based actors. After all, the North never recognized The South as a sovereign nation. As far as the North was concerned, the South was still a part of The United States of America which was suffering in the extremities of the most awful rebellious sedition.

History has a way of playing with us and influencing our lives. Studies have been made of the curious nature of coincidence to be found in some historic lives. Some philosophers sense an invisible hand balancing our “reality” in a strange and ironic twists of fate of taking something of value with one hand while removing from us something of comparable value with another. Dr. Carl G. Jung, a prominent analytical psychologist, would come to call this confluence of coincidences “Synchronicity”. The Greeks called this happenstance “Fate”. I call it “Irony” under these particular historical circumstances. And of course, I, with my typical modesty, consider my opinion to be the most valid. Of all of my many many virtues “Modesty” has always stood out as my finest.

Such an ironic incident of “Fate-Action” played itself out more than a century-and-a-half ago on two separate stages and many months apart from each other. These situations could not have been more dramatically ironic than if they had been written and staged by either William Shakespeare or the great Alfred Hitchcock himself. This particular happenstance involves a Father and Son, of some political fame who both made a name for themselves in: the law, business, and politics, and two actors, brothers in point of fact, whose equally famous lives became intertwined with this other family in a most curious way.

We must now travel back to Jersey City, New Jersey in 1864 which was a very busy spot during the Civil War. Tens of thousands of people, conducting the business of both public life and their private lives, passed through Jersey City every day on their way to somewhere else. Among these travelers-on this one particular day-were a very famous actor rushing his way back to New York where he was engaged to play several roles in several plays of William Shakespeare and a young man in a rush to join his prominent political family in Washington, D. C.

The famous actor’s fellow cast members would be members of his own family, namely his famous thespian siblings, who loved engaging in their favorite, devise of switching the roles they would play night-after-night before a sophisticated New York audience. This switching of roles on a nightly basis posed no problems for them, because this is just what they had done since childhood as a game of play-acting played out in front of the fireplace on chilly nights long ago. More than a hundred plays had inhabited their heads with no difficulty posed by recalling them, line-for-line on a moment’s notice.

The Booths lived, breathed, and soaked-up the language of Shakespeare as if it were ambrosia fed to them by the Gods. Shakespeare was as well known to them as the form of the Latin Mass was known to their family priest. To the members of the Booth Family this reunion before an appreciative New York audience, playing a variety of roles, would be just an exercise in good fun played out each night, and the theatrical run would go on for as long as they wanted it to. The fact that they would make a great deal of money through an extended engagement was merely coincidental to their professional experience. After all, this was the Booth Family, and New York was their very own personal theatrical property.

And as I have previously noted, in Jersey City, New Jersey, at that particular moment on the railroad platform, was young Mr. Robert Todd Lincoln traveling to Washington. Robert was the oldest surviving son of President Abraham Lincoln. At that time, with the deaths of Eddie and Willie Lincoln, he was one of only two surviving of the four sons of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. The Lincolns had brought four sons into the world: Robert, Edward, Willie, and Tad. Of these, only one would survive into adulthood, and that was only because on that particular day on a railroad platform in Jersey City, “Fate” had installed an unlikely yet famous Guardian Angel to secure Robert Todd Lincoln’s life from a horrible and grim extinction under the wheels of a great mechanical beast.

According to Robert Todd Lincoln’s own 1909 account of this incident in New Jersey, the tragedy almost happened when a substantial number of people were buying their tickets for the sleeping cars on the train from the conductor who was perched on the station platform at the entrance to the very sleeping car which young Lincoln had intended to occupy. The platform was narrow at this point where the crowding was taking place, and a lot of shoving began to happen which almost cost the young man his life.

Lincoln then writes, “I happened to be pressed by it [the crowding] against the car body while waiting my turn [to buy tickets]. In this situation the train began to move, and by the motion I was twisted off my feet, and had dropped somewhat, with feet downward, into the open space [between the car and the platform], and was personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out [of danger] to a secure footing on the platform. Upon turning to thank my rescuer I saw that it was Edwin Booth, whose face of course was well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him, and in doing so, called him by his name.”

Later on, both Robert Lincoln’s friends, Colonel Adam Badeau and General Ulysses S. Grant sent Edwin Booth letters of thanks for saving Robert Todd Lincoln’s life in New Jersey. Grant later told Booth that if he could ever do him a favor to just let him know. Edwin Booth was always a Unionist and an admirer of Abraham Lincoln and had twice voted for him. Booth had also admired Grant as the very non-flamboyant savior of the nation. It is also ironic that John Wilkes Booth noted in his diary that he also intended to kill General Grant on April 14, 1865 if Grant had attended the theater with the President on the night that he had assassinated Lincoln.

The facts of Lincoln’s assassination are very well known as are the facts of the army catching up with Booth in the swamps of Virginia and killing him. They need not be retold here. In my opinion Jim Bishop’s book on the Lincoln Assassination is among the best that exists on the subject, and I recommend it as a very good read. It is enough to know that Edwin Booth and his family never fully recovered from what his twenty-five year old brother John Wilkes Booth did on April 14, 1865 in Ford’s New Washington Theater. The Booths felt Lincoln’s loss even more personally than did most of the nation.

John Wilkes Booth had done far more than merely kill a president when he shot Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. Booth changed the entire flow of history for many generations to come. One Hundred and fifty-eight years ago, Abraham Lincoln died at the hands of the youngest brother of the very man who saved his only surviving son’s life. Robert Todd Lincoln would go on to leave a living legacy of his great president-father’s life by the extension of his own life and fathering children, Abraham Lincoln’s Grandchildren, and this was possible only because Edwin Booth was on a train platform on a certain day in 1864 in Jersey City, New Jersey and saw a young man being pushed to his certain death while absolutely nobody else noticed that this event was in progress. How ironic “Fate” can be?

James C. Johnston Jr. is a former Franklin selectman, Franklin High School history teacher, and author of "The African Son," a novel , as well as "The Yankee Fleet" and "Odyssey in the Wilderness," (a history of Franklin, Massachusetts). Article copyright James C. Johnston, Jr. 2023, used with permission.

*************************************************************

The first emancipation proclamation...

April 16 is a holiday in the District of Columbia because on that day in 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed an act of emancipation for the District, a measure introduced and championed by Natick native, one-time maker of shoes, Senator Henry Wilson. It liberated some 3,100 people and was unusual in that it included compensation to the people who claimed ownership of the enslaved individuals.