Image

An oil portrait hangs in the mezzanine level of the Omni Parker House, accompanied by a plaque that identifies the subject as Joseph Reed Whipple, former manager of the hotel. Courtesy/Susan Wilson

Sam Doran | SHNS

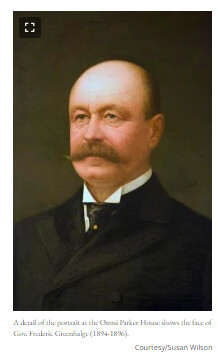

His face gazes down on tourists roaming the halls of two different Boston landmarks, two blocks apart. He casts the same demure smile in both corridors, partly hidden behind a bushy reddish mustache. But in one place, he goes by Fred. In the other, he's been known for decades as Reed.

Who is that mystery man in the spiffy black suit with the gold tiepin?

The News Service noticed the parallel portraiture -- duplicate paintings with a different name on each plaque -- and was puzzled.

Lo and behold, one quiet August day, lobbyist Arline Isaacson stopped by the newsroom with some friends taking a tour of the building. One of them, Susan Wilson, is the official house historian of the Omni Parker House.

The News Service walked Wilson down to the third floor for a look at the capitol's painting.

"That's J. Reed Whipple," she exclaimed as the little group approached the portrait. Then she saw the plaque: Frederic T. Greenhalge.

Susan Wilson, house historian of the Omni Parker House, points to the plaque under Gov. Frederic Greenhalge's official portrait outside the Senate president's office on Aug. 14, 2024. Sam Doran/SHNS

Greenhalge, a popular three-term Republican governor who died in office in 1896, was a native of England and the state's first governor to be born in a foreign country. Some remember him today as the first governor to declare Patriots' Day a holiday.

He served on the Lowell Common Council in the 1860s, city school committee in the 1870s, as a justice of the Police Court for a decade, mayor and city solicitor in the 1880s, member of the House in 1885, member of Congress from 1889 to 1891, and governor from 1894 up until his death in 1896, the first governor to die in office in decades.

But down on School Street at the Omni Parker House, the identical painting is captioned "Joseph Reed Whipple." Whipple, a New Hampshire native, operated three hotels in Boston and was a "culinary innovator," according to Wilson's book about the Parker House, which has a new edition out this month. By 1897, he ran three hotels in Boston and he turned to his hometown of New Boston, N.H. to provide the produce, livestock, and dairy products for his guests.

Photographic evidence of the two men seems definitive: both oil portraits show Greenhalge in his later, perhaps gubernatorial, years.

Puzzled about the case of mistaken identity, Wilson reached out to the Dunfey family, who operated the Parker House for decades. They said their copy was hanging in the same spot -- on the mezzanine level above the lobby -- in the 1980s and '90s. As for where it came from, or who labeled it as Reed Whipple, they couldn't say.

And Wilson said the Parker House's files don't contain any information about where their painting came from -- "nada," she wrote, now calling it "the Portrait Formerly Known as Whipple."

"I must say that most everyone I talked to has seen the painting for ages but never paid any attention to who it was or why it was there," Wilson told the News Service.

She suggested it could have been "an honest mistake" of "mis-labeling" from years past.

Susan Greendyke Lachevre, curator of the State House Art Commission, said she had already known about the second Greenhalge visage hanging down at the Parker House, but never had time to get to the bottom of the case.

Greenhalge died shortly after the opening of the Brigham Extension of the capitol building, Greendyke Lachevre said, and the State House was focused on gathering official portraits of every chief executive to fill the additional display space.

Which portrait was the original? And how did one of them come to be property of a local hotel?

The painting seen today in the State House, just outside the Senate president's office on the third floor, was authorized by the Governor's Council at a cost of $650 and was completed by the artist, W. A. J. Claus, in 1898.

The Boston Daily Advertiser reported that summer that Gov. Roger Wolcott, who had served as lieutenant governor until Greenhalge's death, visited Claus' studio to formally accept the picture. He was joined by the attorney general, a governor's councilor, and personal friends of Greenhalge's like Col. Charles Kenny and Brig. Gen. Edgar Champlin, all of whom gave "expressions of admiration" for Claus' work.

But it wasn't the first time Claus had painted this subject.

Ten months after the governor died (and the state spent $11,800 on his funeral), dozens of his closest friends gathered for a special dinner at the Parker House. They were there to found a new "Greenhalge Club" dedicated to his memory.

A full-length oil portrait of Greenhalge was displayed behind the head table at the banquet. It was painted by the same artist, W. A. J. Claus, according to multiple newspaper accounts, and the frame was draped with the U.S. and state flags.

"So we have the replica," Greendyke Lachevre told the News Service on Tuesday, informed of the January 1897 date attached to the other painting. "It doesn't say that it's a copy, or a replica ... which I thought was interesting," she added, referring to the State House picture. "But you found that that Parker House one was 1897."

In an account from the time, the Boston Globe said the painting at the banquet belonged to Col. Charles Kenny, who had served on Greenhalge's staff, and that Kenny "will soon place the portrait on exhibition at one of the art galleries in this city."

Kenny's obituary later called him "one of [Greenhalge's] most intimate friends." Whether the portrait hanging today in the Parker House mezzanine is the same as Kenny's canvas cannot be said for a certainty.

"It is a little weird," Greendyke Lachevre said of the second portrait. "Because, why does the Parker House need a portrait of Greenhalge? That's the whole question, I think."

In life, Greenhalge appears to have been partial to the hotel and had numerous speaking engagements there. He also situated his election night headquarters at the Parker House in 1893, celebrating his first victory in a private parlor on the second floor, and he was back at the Parker House on Election Night 1895 as he cruised to a third term.

"They found out that they had elected a man to be governor who, while he occupied the chair, would be governor alone," Judge George Field Lawton later wrote, "in whose courage, justice, and wisdom they could confide; and they kept on electing him until he died."

He also helped save the hotel from burning down.

According to an account from the Lowell Daily Sun, it was early in the morning of April 7, 1895 when a Boston Fire Department captain was trying to run a hose through a window to carry toward a fire in the Parker House. The occupant of Room 14, "a distinguished looking gentleman," offered to help and opened his window.

The firefighter went outside to pass the hose up to the man, and by the time he had gotten back inside, he "found that his volunteer assistant had taken the line of hose through his room out to the fire, and had it already put to use." The fire was extinguished with little damage.

"Shortly afterward, when Capt. Quigley went back to the room through which his hose ran, he found it guarded by two policemen, and was informed that it was the governor's room," the Sun reported. "His surprise can be better imagined than described, for he realized that the gentleman who had so ably assisted him was no less important a personage than His Excellency, the governor."

The Parker House was the site of Greenhalge's final speech, on Jan. 28, 1896, at the 20th annual meeting of the Boston Druggists' Association. It was his "last public utterance," according to his biography by James Ernest Nesmith.

Ironically for this case of mistaken identity, a frequent celebrity guest like Greenhalge may well have been acquainted with the hotel's owner, Whipple. And the chicken, eggs, cream, milk, and pork consumed by Greenhalge and his political pals in the Parker House dining room would have been raised up north at Whipple's state-of-the-art farm in New Boston, N.H.

Today, Greenhalge watches over not just the hectic halls of the State House, but the comings and goings of one of Boston's historical hotels. He knew both spots well, and perhaps had them in mind when he penned a few lines of poetry, which are reprinted in his biography:

I love the busy haunts of busy men:

The strife of courts, the bustle of the marts,

The gathered life of all these earnest hearts

Might fire Prometheus' fainting soul again!

Wilson said last week that the Parker House's management is thinking of swapping out its erroneous plaque for a new sign -- one that "tell[s] the story of mistaken identity."

Reporter