Image

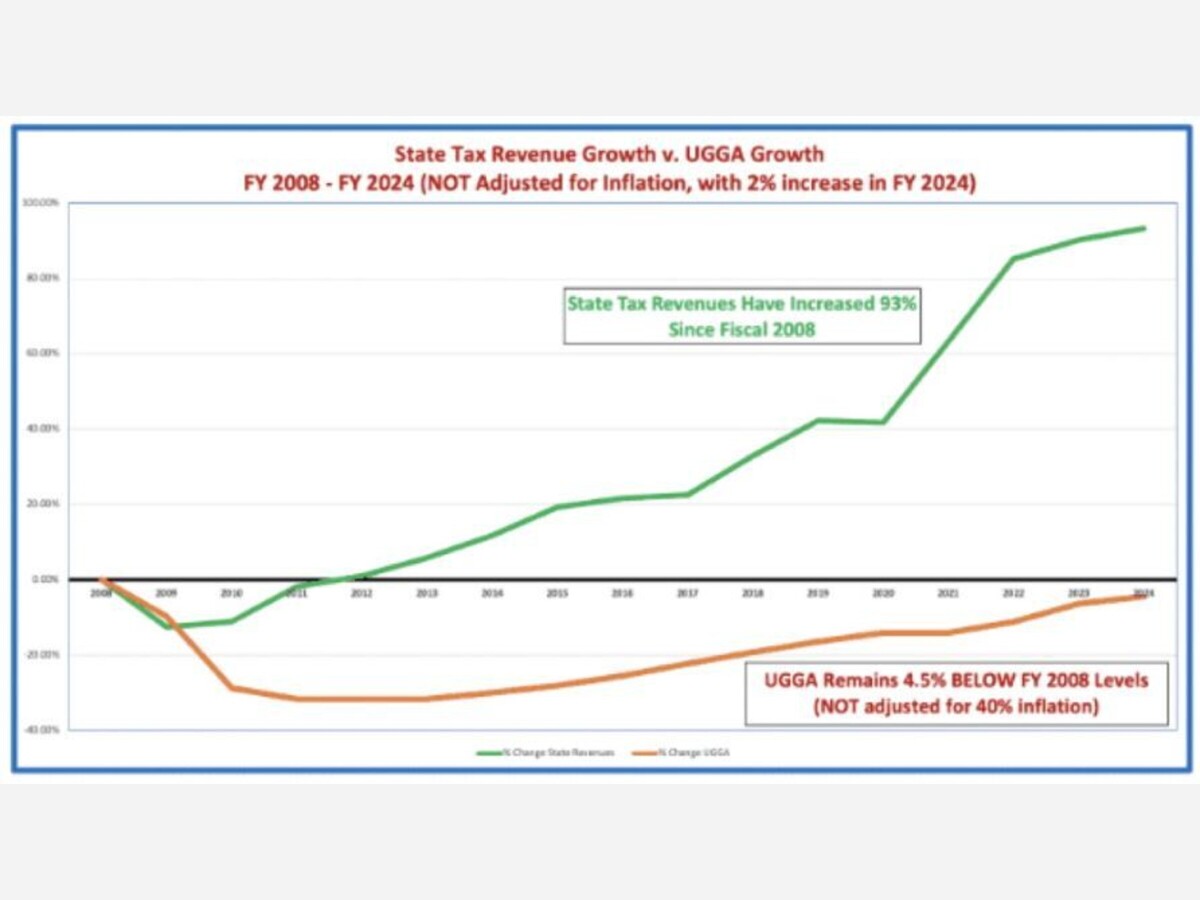

The Massachusetts Municipal Association said state revenues have grown about $18.9 billion since fiscal year 2008, but Gov. Maura Healey's fiscal 2024 budget would keep unrestricted general government aid to cities and towns at about $59 million below its 2008 level. [MMA]

Chris Lisinski| State House News Service

The figure in the corner office is different this time around, but municipal officials will try in 2023 to repeat their success last year in convincing the Legislature to pack tens of millions of additional local aid dollars into the state budget than the governor proposed.

Massachusetts Municipal Association leaders pitched lawmakers Monday on their request for $1.3 billion in unrestricted general government aid in fiscal year 2024, representing a $75.5 million increase or 6.13 percent over the current year's budget that would inch the state closer to fully restoring the amount of funding offered before Great Recession-era cuts.

Reopening debate about state government's obligation to share revenues with municipalities at a time when many cities and towns still have sizable pots of unspent federal money, MMA Executive Director Geoff Beckwith said Gov. Maura Healey's proposal to increase unrestricted local aid by $24.6 million or 2 percent is "too low."

"It is so far below inflation and the general costs that communities are struggling with that it would backslide communities' ability to support municipal services," Beckwith said at a Joint Ways and Means Committee hearing in Amherst.

Cities and towns are aiming high: their goal would represent more than three times as much as Healey sought in her budget and nearly four times as much as the forecast state tax revenue growth of 1.6 percent baked into the spending plan.

For years, former Gov. Charlie Baker and lawmakers agreed to boost unrestricted general government aid, or UGGA, by the same rate as the anticipated increase in tax revenues. Beckwith said that plan "actually worked" until 2020, but now, cities and towns no longer believe the revenue-linking approach is sufficient in part because actual state tax collections have far surpassed the forecasts used in budget building.

Since FY21, he said, state revenues have grown by 18.38 percent, an unprecedented period of growth that blazed past expectations and enabled lawmakers to address an array of spending demands. If lawmakers enacted Healey's unrestricted local aid proposal, it would mark an 11.3 percent increase over FY21, reflecting a pace that MMA warns has "started to leave local governments behind."

In fact, Beckwith said, Healey's budget bill would keep the total amount of unrestricted aid below its "high water mark" hit more than a decade and a half ago.

Back in fiscal year 2008, the "lottery aid" and "additional assistance" line items -- which state government later combined to form the current unrestricted general government aid line item -- added up to about $1.31 billion.

The next year, in the throes of the Great Recession, Gov. Deval Patrick slashed some local aid spending with 9C budget cuts, dropping combined unrestricted aid to about $1.19 billion. Beacon Hill continued to trim the annual UGGA appropriation for the next few years, reaching a low of nearly $834 million in fiscal 2012.

Despite almost continuous growth since then, unrestricted aid has not fully rebounded, and Healey's budget bill would fund the line item with about $59 million less than the combined fiscal 2008 figure.

"That's not even figuring in the impacts of inflation, which is about 40 percent during that time. So that would mean ... local aid has a buying power that's 40 percent lower," Beckwith said. "That's not a complaint. It's just to say, when you say, 'Why are communities struggling to balance their budgets in so many parts of the state?', it's just because of that fiscal reality."

An analysis that the MMA presented Monday shows that state tax revenues since fiscal year 2008 have increased about $18.9 billion.

Beckwith suggested Beacon Hill use a rolling three-year average of state tax revenue growth to craft its local aid increases, calling that a "more accurate, stable and appropriate calculation" with "much less volatility" than a single-year projection.

Municipal leaders are not the only ones who have pointed out flaws in the way that state government calculates unrestricted local aid. The business-backed Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation has also called for lawmakers to reconsider their approach, suggesting one alternative could be to base UGGA increases on last year's tax revenue growth instead of the projected growth for next year.

"The idea of ensuring that local aid tracks the state economic growth was and is a good one. I think the Baker administration made a ton of progress on that. What we've seen is that when we're basing on projected revenues, there's a lot of opportunity to get it wrong," MTF President Doug Howgate told the News Service. "Putting in place something that uses look-back revenue or economic growth data would solve some of those issues."

MTF also took aim at the method used to distribute dollars to individual cities and towns. The group said each municipality's annual UGGA allotment "is based solely on the amount received in the prior year," meaning funding levels "defy all logic and can exacerbate inequities."

"UGGA funding ranges from $397 per capita to less than $30 per capita," MTF wrote in a preview of issues to watch this term. "Somerville receives $360 per resident, while Framingham, which has a similar population and a lower income per capita, gets $159 per resident. The formula has been in dire need of review for years and the time has come to rationalize the distribution."

Lawmakers demonstrated a willingness last year to bulk up the amount of unrestricted aid, which cities and towns can use at their discretion on a wide range of services including public education. Baker originally proposed boosting UGGA by 2.7 percent, and the Legislature doubled that increase to 5.4 percent.

Cities and towns are pushing for more unrestricted state aid after receiving a major influx of cash in one-time federal aid packages during the COVID-19 emergency. Municipalities and counties got roughly $3.9 billion in combined funding from the American Rescue Plan Act and the CARES Act, according to the state Federal Funds Office.

It wasn't immediately clear Tuesday how much of that money remains unspent. State government does not track local spending of ARPA dollars. Large municipalities are required to report spending to the federal government quarterly, while most others report annually.

The latest annual spending data published by the U.S. Treasury covers the period ending March 31, 2022, nearly a year ago, and the next reports are due in April.

Beckwith said MMA as a group "doesn't have the resources to track ARPA or ESSER funds." He said cities and towns received between $105 and $299 per resident in ARPA funds, calling that "a very small amount" of overall ARPA dollars.

"Regardless, these funds should not be used to fund existing operations, as these are one-time funds that are intended to fund one-time investments, primarily in a few categories of allowable uses," Beckwith said in a statement to the News Service. "Using funds to replace lost revenue could temporarily support general services, but that would be extremely risky, because it would create a steep fiscal cliff in future years. Note that the state is not using its ARPA funds to fill holes in its operational budget for this very reason, and is using the funds to leverage important one-time investments in environmental capital, housing, workforce development, and other priorities. That's what communities are doing locally."

"ARPA is not a replacement for local aid, and shouldn't be used to support existing services, as that would create deep budget deficits in future years, and jeopardize budget stability in the long run," he added.

Only about a third of the roughly $2.9 billion Massachusetts that communities received in Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, money had been spent as of November, according to the EdImpact Research Consortium.

Healey also proposed several other sizable local aid increases, particularly for K-12 education. Her budget bill calls for a $586 million or 9.8 percent increase in Chapter 70 aid, representing full funding of the 2019 education funding reform law known as the Student Opportunity Act, plus a nearly $15 million or 18 percent bump in money to help transport students to regional school districts.

Beckwith urged lawmakers to weave in about $19 million in additional Chapter 70 funding to give every school district at least $100 more per student, warning that 119 districts -- collectively serving about 275,000 students -- are currently in line for "minimum aid" growth of $30 per student.

MMA called the minimum aid increase "simply inadequate to maintain existing programs and services."

Another pressure point on municipal minds is the required 5.6 percent increase in local spending on school budgets that would stem from Healey's budget. Beckwith said that figure surpasses the 3.7 percent average growth in municipal revenues in the past three years, creating difficult decisions in city and town halls.

"They'd have to take money away from the recreation programs, the library programs, public safety, public works in order to fund their increase in the minimum required contribution," he said.

The House Ways and Means Committee will likely roll out its rewrite of the FY24 budget bill in the next three to four weeks, which will offer an early hint of how willing top Democrats are to embrace the MMA's request.

Hesitation to bump up local aid in the House does not spell doom for cities and towns, however. Last year, the House's original budget bill mirrored Baker's aid increase, and the Senate's proposal to double the UGGA growth wound up in the final conference committee version that Baker ultimately signed.

-END-