Image

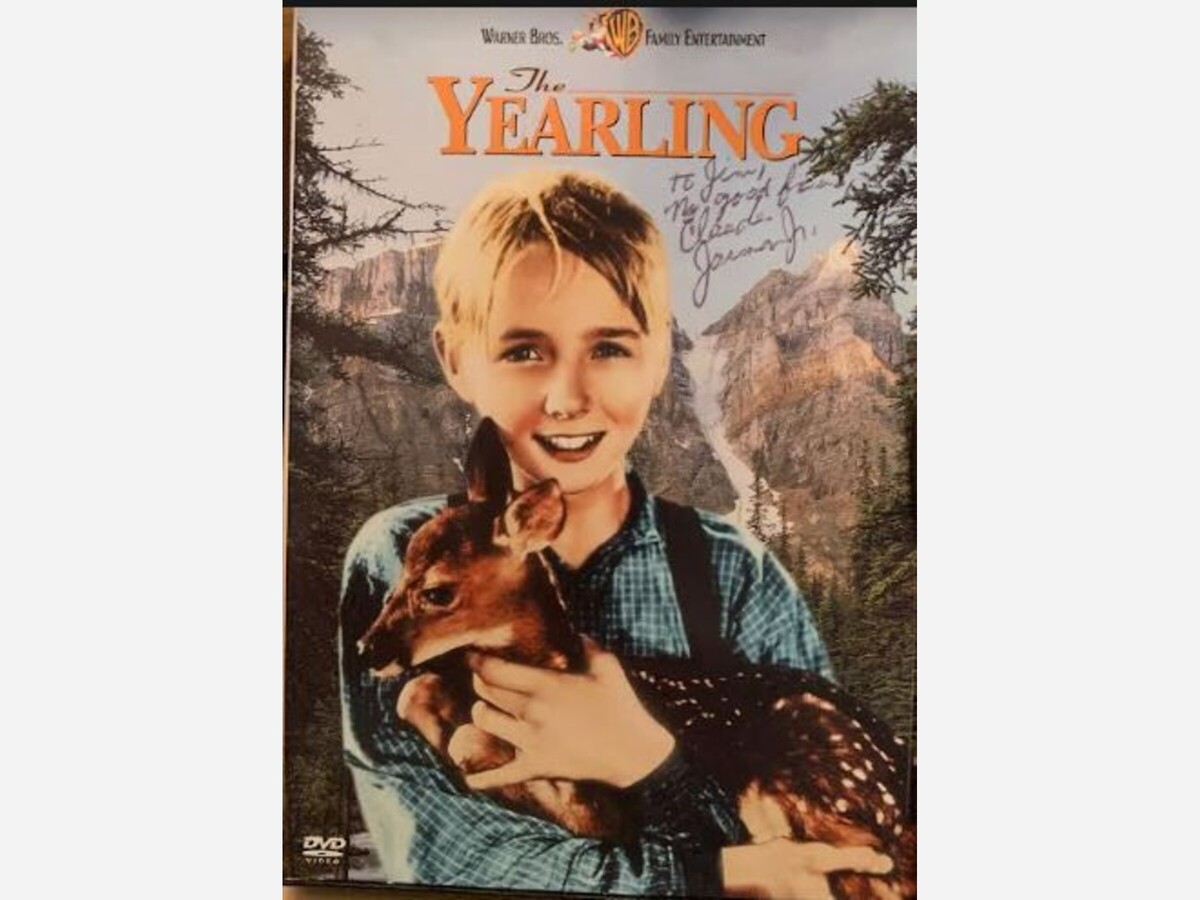

By James C. Johnston Jr.

On Saturday, I called a friend, and as is my custom I sang Happy Birthday in honor of his 90th day of natality. This time I sang it into an answering device then hung-up. Yesterday I received a phone call from my friend thanking me for my congratulating him on the first anniversary of his 89th Birthday. Last year, I had wished him a Happy Entering of his 90th Year! He had been amused but at the same time some-what put off by that salutation. My friend, in this case, is a very distinguished gentleman and Academy Award winning actor Claude Jarman Jr.

I have been lucky to have had some very good friends in my lifetime, and one of these living treasures is Claude Jarman Jr. If his name is familiar to you it is because he was a really great young actor whose film career began in the mid-1940s, quite by accident, and the fact that he looked right for the part of his country-boy character, and largely because he needed a haircut!

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings wrote a book back in the 1930s which became an overnight classic. It was called The Yearling. It was about a young boy named Jody Baxter who was living with his family in a very swampy part of Florida in the years after the Civil War. He was the only surviving child of a poor subsistence farming couple who desperately worked away trying to farm under very challenging circumstances.

Against this background, a very imaginative child of nature whose father was very sympathetic lived a life on an Everglades farm situated on land referred to as Islands which was a lonely setting yet filled with the magic and fantasy provided by his wonderful imagination and his quest for a pet. As warm as his his father was, his mother was cold, because she was afraid to give her heart to her only surviving child, because she knew all too well that he could be taken from her as were all of her previous babies.

In the course of the story, Jody’s father is bitten by a rattlesnake, and Jody is forced to kill a doe with a fawn to secure organs from the doe’s body to draw the poison from his father’s wound. Thus Jody’s father’s life is saved. Jody asks his father if he could rescue the fawn and raise it, because he desperately wants a friend/pet, and the fawn was now orphaned and at the mercy of nature itself. Over his wife’s strenuous objections, Jody’s father tells the boy to go out and fetch the fawn back to the house.

The rest of the book is a riveting tale of the struggle for survival and the coming of age of this young Florida boy and the life-lessons to be learned in living on the edge of the primitive frontier. The book was, and indeed is a pure joy to read. It stands the test of time in its ageless lesson to be learned in the maturation of a beautiful and sensitive human soul on what was still a wild part of this country newly emerged from The Civil War of a bit over a decade past.

The beauty of the book was not lost on Hollywood, and it was purchased from the author in the mid-1930’s to be made into a film which would star Spencer Tracy as Jody’s father, Penny Baxter. Filming began and then ran into one snag after another. It was rumored that Tracy hated the project which was eventually put on hold and then abandoned altogether as war clouds formed in those troubled years before the eventuality of Pearl Harbor and our involvement in World War II.

More than half a decade after The Yearling project had ended, the war was winding down. Before the film’s release, the war would end with a justly celebrated victory over the evil Axis powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan whose final defeat was the direct result of two huge atomic explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a now a new world into which The Yearling was to premier filled with anxiety which was fully justified by the circumstances of the New World Order where we all would live under the threat of thermonuclear annihilation as the result of the political and cultural conflict between the dominant United States and the other super power, The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics..

Once again in 1944, The Yearling was resurrected by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a project for producer Sydney Franklin based on a new screen play of Rawling’s book by Paul Osborn, and most importantly of all, this monumental effort was to be directed on authentic Florida locations by the great Clarence Brown.

Now Clarence Brown was no stranger to our area of New England. Brown was born in Clinton, Massachusetts in 1890, but he was educated at Knoxville High School and University of Tennessee. But Brown knew the Massachusetts area well from childhood, and he had even filmed here in 1935 in and around Grafton, Mass. when he made the film version of Eugene O’Neil’s Ah Wilderness.

Brown was an innovative force of nature who used such mechanisms as looping to refine the quality sound and spoken dialog way beyond anything previously experienced in cinema. His filmography includes dozens and dozens of truly great classic films such as: Trilby [1915], Flesh and the Devil [1926], and 1930 Academy Award nominated for best director films: Anna Christie with Greta Garbo, 1931 nominated films Romance and A Free Soul, and he should have been nominated for Anna Karenina with Garbo in 1935, but alas he wasn’t.

Brown was nominated again by The Academy for The Human Comedy in 1943, National Velvet in 1944, and The Yearling in 1946, but in spite of these several nominations the only Academy Awards given The Yearling were for sound to Douglas Shearer and Claude Jarman Jr. Claude’s Oscar was a special Academy Award for his outstanding portrayal of Jody Baxter. It was presented to him by Shirley Temple who was herself a previous winner. In those days these special awards were shorter than the awards presented to older actors, and Shirley Temple, Claude, and other recipients asked The Academy to correct this practice. As a result Ms. Temple, Claude and the handful of other honorees received full size status of Oscar. So now Claude has two awards of two different sizes.

To this day, to see Claude’s acting in this great film is totally amazing. He is on screen almost the entire length of this long and episodic film. His portrayal of Jody is totally credible to the point that you are no longer watching a child actor. You are in fact watching an authentic Southern boy in the real emotional throes of coming of age surrounded by the Everglades a hundred and fifty years ago. His performance is so real that the time flies by and you can even forget that what you are seeing is a movie.

Claude was also totally credible in Intruder in the Dust. In Clarence Brown’s making of this film in Oxford, Mississippi in 1949, we can witness social history, because, this groundbreaking film was one of the first to introduce the theme of racism which had been a real, but unspoken of issue boiling just under the skin of American awareness which was about to burst onto the American scene with full dramatic and historic force over the following decades of American life.

Next time in Part 2 of this series, I will tell you how Clarence Brown discovered Claude and made him the star of his first film.

James C. Johnston, an author and a retired Franklin educator, is a frequent contributor to Franklin Observer