Image

The state's 35-year-old debt ceiling is again causing a bit of claustrophobia for state finance experts, who this year recommended a lower-than-usual increase in state borrowing for fiscal 2026.

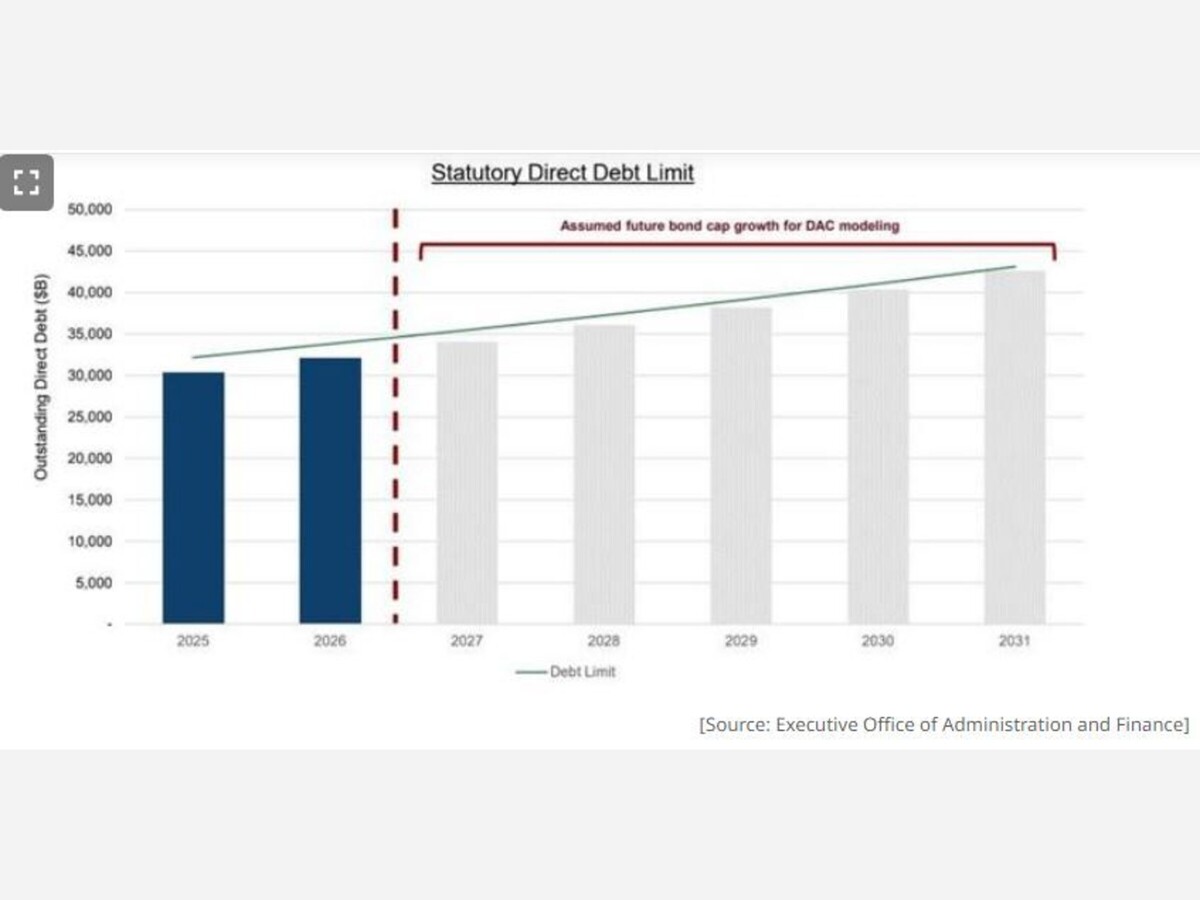

The statutory debt limit caps the overall level of outstanding direct state debt and by law increases 5% each year. The limit is fixed at $32.188 billion in fiscal 2025, and while financial statements published last month show Massachusetts has about $32.643 billion in total debt, about $27.558 billion of it is subject to the limit.

That limit and the shrinking headroom beneath it is "the biggest constraining factor" as the Capital Debt Affordability Committee met through this fall to determine the prudent level of debt for the budget year that starts July 1, 2025.

The non-binding report comes at a time when the state's growth strategies rely on big capital spending plans, including massive new housing and economic development laws and a forthcoming environmental bond bill, and as inflation and especially rising construction costs eat into the buying power of capital budgets.

The group of executive branch appointees voted this month to recommend that the state could increase the bond cap for fiscal year 2026 by $110 million -- less than the $125 million annual increase that served as something of a baseline for much of the last 15 years -- to $3.227 billion. The debt ceiling will rise to roughly $33.797 billion in fiscal 2026, which begins July 1, 2025.

"Direct debt, I think this is something that we all agree is the the biggest constraining factor in this year's analysis," Kaitlyn Connors, the Executive Office of Administration and Finance assistant secretary who chairs the committee, said as she summarized the recommendation the group voted for unanimously. "At the end of last fiscal year, we were about 89% at that direct debt limit, and that's where we've been, relatively in that ballpark, in recent years. However, modeling suggests that as you increase the bond cap year over year, you do start to get closer and closer to that direct limit. And so when we're looking at a number of scenarios, it looks as though we would hit very close to that limit somewhere in 2031 under various scenarios."

The group's recommendation is for a $110 million increase in fiscal 2026, but the experts also said their analysis "suggests an annual year-over-year bond cap growth of $110 million in fiscal years 2026 through 2056 is affordable and sustainable assuming modeling input assumptions remain relatively in line with actuals," they wrote in a letter that was sent to the governor.

And keeping annual increases at $110 million would avoid the potential problem of hitting the debt ceiling, though it "would result in Commonwealth outstanding direct debt reaching 99% of the direct debt ceiling around 2031, where it will stay until 2037, after which point the buffer between projected actual outstanding direct debt and the limit begins to increase."

At the end of fiscal 2024, the state's outstanding debt totaled about 89 percent of the limit, down from 98 percent in fiscal 2016. State finance officials said this month that the state was at roughly 86 percent of the limit as of early December, though additional bond issuances are planned for the remainder of the fiscal year.

Massachusetts was projected to bump up against the debt ceiling it has had since 1989 for the first time ever in fiscal 2017 when lawmakers, on the final day of formal sessions in 2016, exempted $1.86 billion of borrowing for the Rail Enhancement Program from the statutory limit to give the state more breathing room.

The Executive Office for Administration and Finance established a debt affordability policy in fiscal 2009, and the Capital Debt Affordability Committee was created by legislation in 2012. The committee has generally considered $125 million the maximum annual increase in the bond cap.

After at least five years under Gov. Deval Patrick of $125 million increases, Gov. Charlie Baker's administration started off by making no increase to capital spending for fiscal year 2016 and then gradually ratcheting up capital spending by slightly more than 3 percent each year from fiscal 2017 through fiscal 2021. Fiscal 2022 saw the return of the $125 million annual increase again until the committee's suggestion for fiscal 2025.

When it made its recommendation a year ago that Massachusetts could afford to increase general obligation debt for capital spending by $212.2 million or 7.3 percent in fiscal year 2025, the committee said the larger-than-usual increase was warranted because escalating construction costs had "significantly eroded" the purchasing power of the state's capital investment plan.