Image

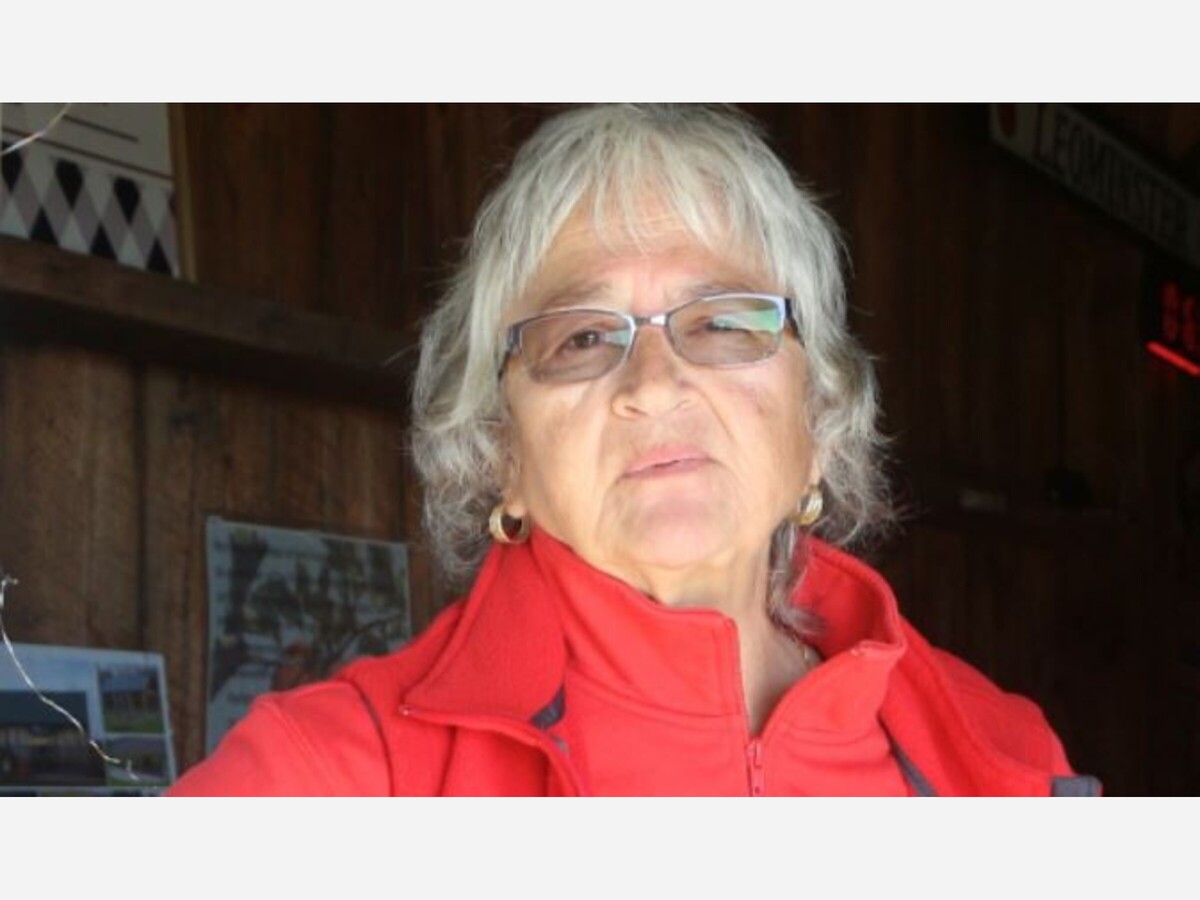

Joanne DiNardo operates and manages the Sholan Farm along with 75 volunteers. For the farm to reach its long-term viability goals, DiNardo is hoping to build a pavilion and other infrastructure to attract more customers. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)

by Rebeca Pereira, CommonWealth Beacon

April 17, 2025

Twice a year, Kathryn Szerlag, a professor of soil and water chemistry at Texas A&M, traverses the country to reunite with relatives on their family dairy farm in Northbridge, Massachusetts.

“All of [my research] came from playing in the cow manure,” she reflected on a Friday in December, the day before boarding a flight home for the holidays. “That was my daycare: a pair of rubber boots.”

The farm provided a singular education. Before academia, Szerlag was a country kid entrusted with testing the butterfat concentration of the milk of 300 cows. It was there, wading in dung, that she ultimately found her subject matter: the environmental degradation wreaked by high phosphorus levels in animal manures.

The farm has remained in agricultural production for four generations, bulwarked by Szerlag’s father, her late uncle, Frank, and his son, Stephen. But it hasn’t persisted unscathed.

Kathryn Szerlag’s family, which has owned and operated a dairy farm in Northbridge, for generations, had to sell a portion of their land to a developer to make ends meet. (Courtesy of Kathryn Szerlag)

Kathryn Szerlag’s family, which has owned and operated a dairy farm in Northbridge, for generations, had to sell a portion of their land to a developer to make ends meet. (Courtesy of Kathryn Szerlag)More than a decade ago, the Szerlags sold a field and a wooded swath of land to a real estate developer. Public records show the development, Presidential Estates, carved into the erstwhile farmland a cul-de-sac of single-family homes. In compliance with the town of Northbridge’s requirement that open space account for at least one-third of a development, the remainder of the land was deeded to the Metacomet Land Trust in 2019.

The Szerlags' land sale isn’t an uncommon choice. Census data indicate that, with their backs against the wall, many farmers sell fragments of their land to support the rest of their business. Since 1997, the number of Massachusetts farms smaller than 50 acres has swelled while the number of larger farms has plummeted.

Some farmers sell their land because there is no one to take over the family business — in Massachusetts, there are three times as many farmers over the age of 65 as under the age of 35. Others do so because the price of agricultural production has become too burdensome. An acre of farmland now costs $14,300 in Massachusetts — third most expensive nationally after New Jersey and Rhode Island. Over the past three decades, the cost of farming itself has nearly doubled.

The latest data from the US Agricultural Census show more than 100,000 acres of farmland in Massachusetts have been lost since 1997.

Almost a quarter of those acres was lost between 2017 and 2022. That’s an average of losing just under 15 acres of farmland a day, approximately 15 football fields end zone to end zone, roughly double the rate of farmland loss nationwide.

The American Farmland Trust, a nonprofit working to conserve agricultural lands, estimates that, without stronger protections, the state stands to lose between 50,000 and 90,000 acres of farmland by 2040 — a possibility Massachusetts may manage to thwart as the levers of the state Legislature begin to arc toward more aggressive farmland preservation.

More than a way of life, farmland loss across New England risks the region’s food security and the environmental contributions of farmers applying regenerative, climate-conscious agricultural practices. These approaches restore soil health, sequester carbon, improve water retention, and reduce erosion, helping the region withstand extreme weather events as the effects of the climate crisis worsen. And it is in service of these stakes that, on Beacon Hill, a commission is poised to issue a series of recommendations for confronting the 21st-century challenges facing farmers in Massachusetts.

At the Community Harvest Project, a nonprofit farm in Harvard, Tori Buerschaper trailed behind a cohort of volunteers weaving through rows of apple trees. She watched on as they sorted first grade apples from those that were blemished or bruised, bagging good ones by the dozen and setting gnarled ones aside to send to the cider mill.

The nonprofit designed this workflow to not only bridge the disconnect between consumers and the food they eat but to illuminate the realities of hunger in Massachusetts.

“We luckily live in one of the most prosperous states in the US, where it's easy to think there isn't hunger,” Buerschaper said. “When people have limited income, they're forced to pick and choose. The thing you kind of get to last, or that you can more easily cut out, is food.”

So far, the model they built has been a success. In 2023 alone, CHP hosted more than six thousand volunteers at its orchard in Harvard and at its 15-acre farm in Grafton. Together, each year, the two locations yield 300,000 pounds of apples, cabbage, tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, squash and other produce that’s sold to 26 partner agencies committed to combating food insecurity.

But the nonprofit’s operation wasn’t always this expansive.

In 2014, CHP was farming on leased land when donors in Harvard gifted the nonprofit 75 acres of orchard and rolling hills after more than 50 years of private ownership.

Land is in high demand in the central Massachusetts town, and Buerschaper explained that her nonprofit “could have made the decision to sell it to the highest bidder.”

“It’s very likely that would have been a developer over a farmer,” she said.

Years later, standing watch over the orchard’s undulating hills, these considerations seem to Buerschaper a distant reality. Now, owing to the state’s Agricultural Preservation Restriction program, or APR, the nonprofit’s land is safeguarded against any future development.

If a farmer is looking to buy land and conserve it — or protect land they already own from future development — the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture, or MDAR, will pay the farmer the difference between the land’s market value and its developable value. From then on, the state owns an easement on the land, meaning it can dictate the terms of any future land sale and use, ensuring that land remains in agricultural production in perpetuity.

Since it was established in 1977, the APR program has conserved more than 950 parcels — or 70,000 acres — of farmland across the state, and it has served as a template for farmland conservation programs across the nation. These deed-restricted acres will be farmland forever.

In 2023, CHP closed on an APR totaling almost $3 million, money that CHP’s board of trustees chose to invest. Buerschaper said the nonprofit plans to withdraw $80,000 from its investment portfolio per year. She said the funds have helped ease financial fears about “the growing pains [that] never really stopped.”

APR is one of the best tools the state has to preserve farmland. Other programs exist under the breadth of MDAR’s purview: a land licensing program for state-owned farmland; a succession-planning workshop, Farm-Pass, to help aging farmers transfer their business to a new owner; and numerous grant opportunities designed to keep farms viable and farmers employed.

But these programs are only a treatment, not a cure, for the seemingly insurmountable financial hurdles which push many farmers to sell. APR money can run out with time, and enrolling in the program to begin with may not even occur to farmers needing an immediate remedy for their financial troubles.

The application process requires patience and foresight: Once a farmer applies to the program, staff at MDAR and a third-party appraiser assess the farm’s resource value and work with the landowner to come up with a funding plan. The state’s Agricultural Lands Preservation Committee then votes twice before giving the transaction final approval. In some cases, farmers can opt in to receive federal funding from the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, extending the application process even further.

While MDAR is bound to this existing procedure, which can take years, developers are not.

With deeper pockets and greater agility, developers tend to have an advantage over the state’s interest in preservation, especially as the business of farming becomes more and more untenable.

In 2016, Sean Stanton purchased North Plain Farm in Great Barrington, land that had been protected by the APR program for decades and in agricultural production for centuries. Then, three years ago, he closed on another APR that allowed him to purchase a 75-acre property a quarter mile down the road.

MDAR encourages farmers to look for local partners to help fund up to half of the value of their easement. In Stanton’s relatively anomalous case, the town of Great Barrington contributed $92,000 to the purchase. Meanwhile, MDAR awarded him $828,000.

The state’s near-million-dollar investment in North Plain Farm wasn’t the first or the only support it gave. Stanton has received grant funding from MDAR’s Farm Viability Enhancement Program to purchase new farm equipment, and he’s taken business classes through the agency’s Tilling the Soil of Opportunity program. The funding he’s received from the state has helped support his business, but it hasn’t inoculated the farm against financial distress.

Sean Stanton has used the APR program. In 2016, Sean Stanton purchased North Plain Farm in Great Barrington, land that had been protected by the APR program for decades and in agricultural production for centuries. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)

Sean Stanton has used the APR program. In 2016, Sean Stanton purchased North Plain Farm in Great Barrington, land that had been protected by the APR program for decades and in agricultural production for centuries. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)Until he decided to go back to school, enrolling in a social work master’s program at Westfield State, Stanton said he was “for years, digging a bigger financial hole.” Now, he hopes to practice as a clinical social worker as soon as 2026. He’ll become one of more than half of the state’s farmers who do not list farming as their primary occupation, and he wonders what will happen when his well of APR funds runs dry.

On the farm, he teased a joke about how farmers make money.

“This is so depressing,” he warned. “How do you make a million dollars farming? Start with two.”

For farmers who have held their APRs for longer than Stanton, concerns about their businesses’ longevity are even more acute.

In July 2001, Dean Mazzarella stood on Pleasant Street, where the road bends and slices across Sholan Farm in Leominster, and accepted a check from the Commonwealth to purchase the farm and to conserve it as farmland in perpetuity.

Mazzarella has been mayor of Leominster for more than 30 years, and by 2001 he had already seen numerous farms in and around the city succumb to a fate that Sholan Farm only narrowly escaped. Over time, Sholan’s owners aged and stopped farming the land. When the land entered the real estate market in 1999, developers drafted a plan to convert the farm’s 167 acres into houses.

That’s when the possibility arose for the city to buy the land instead. With support from the state, the city closed on an APR that totaled $4.75 million. MDAR contributed $2.6 million toward the purchase, and the Department of Conservation and Recreation funded another $1.6 million to support the farm in conserving reservoirs on the land. The city pitched in $500,000 to purchase the land and fundraised the remaining value of the easement through Friends of Sholan Farm.

In the process, Mazzarella found an ally in Joanne DiNardo, who now operates and manages the farm alongside 75 volunteers. DiNardo said the lump sum infusion from the state and other partners “helped us save the farm.” But for Sholan to meet its long-term viability goals — to expand its offerings, to stay open 12 months out of the year, to build a pavilion and other infrastructure that could attract more customers — DiNardo said a “one and done” investment won’t be enough.

Joanne DiNardo (left) and Leominster Mayor Dean Mazzarella’s first season at Sholan Farm saw eight eight apple varieties harvested. They now harvest 37 varieties. Mazzarella said the city “rescued” the farm in 2001, when it was slated to be sold to a developer and converted into 176 housing units. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)

Joanne DiNardo (left) and Leominster Mayor Dean Mazzarella’s first season at Sholan Farm saw eight eight apple varieties harvested. They now harvest 37 varieties. Mazzarella said the city “rescued” the farm in 2001, when it was slated to be sold to a developer and converted into 176 housing units. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)Unlike privately-owned farms enrolled in the APR program, city-owned farms like Sholan aren’t eligible for APR improvement grants that could help keep the business afloat for years to come.

If Sholan’s APR money runs out and the business isn’t otherwise profitable, the city could feasibly sell or lease the land to other farmers, maintaining compliance with the terms of the easement. The land would stay in agricultural production, but the city, like all farmers who sell in the face of financial hurdles, would pay the cost.

“Maybe more cities would buy orchards, you know, farms, and maybe get schools to run them or volunteers, like we do. But after you buy the land, you're on your own,” Mazzarella said. “So, what's the incentive?”

Beyond these pastoral terrains and panoramic fields, over the course of the last two years, a coalition of legislators and state agricultural leaders heard testimony on the future of the Commonwealth’s agricultural sector.

Led by state Sen. Jo Comerford and state Rep. Kate Hogan, the 21st Century Agriculture Commission is expected to recommend a slate of reforms aimed at tackling climate change’s impact on farms and the demand for educational and technical assistance for farmers. Their recommendations, previewed at a public hearing in July, also address the state’s farmland freefall and the financial obstacles facing farmers. Initially scheduled to be released in December, the commission’s report received a year-long extension and will be released to the public before the end of 2025.

Crucially, the commission is poised to recommend including farms smaller than five acres in the state’s existing agricultural lands tax exemption, a change that could only be accomplished by amending Chapter 61A of the state constitution.

This measure, a reflection of how “farming has changed in Massachusetts,” is also a matter of equity for Winton Pitcoff, deputy commissioner of MDAR. “It’s important that farmers who have been excluded for a variety of reasons — particularly farmers of color through systemic racism that can’t afford large tracts of land — it’s important that we make sure that they can farm if they want to. That means making sure they can access land.”

Farmland preservation has already secured an important step forward with a measure enshrined in the multibillion-dollar economic development bond bill. For months, the must-pass bill idled unresolved following the end of the formal session, but lawmakers returned for a vote and sent the bill to Gov. Maura Healey’s desk in November.

The measure authorizes MDAR to buy, protect and sell farmland, giving the agency enough purchasing power and agility to beat out developers vying for flat, open land unlike the APR program, which is a safety net that requires foresight and patience.

“It’s pretty appealing when someone is able to give you a check right on the spot to buy your land. That’s usually a developer. That’s what leads to conversion,” explained Pitcoff. “It’s not like the department wants to become a landlord and buy lots of land. What this does is give us the flexibility to purchase land more quickly.”

The agency will need to build its buy, protect and sell program from the ground up, writing new regulations and advocating for funds from the state budget each year.

Also included in the economic development bond bill is an initiative to cut some of the red tape around non-agriculture activities on APR farms – a change that will help forge alternative revenue streams for these businesses. As long as the land in question remains in full-time commercial agriculture, MDAR may grant farmers special permits for hosting weddings, classes, charity runs, and other agritourism events adjacent to actual agricultural production.

Previously, farmers like Tori Buerschaper, who hosts a 5k fundraiser at CHP, would need to apply for a discreet permit with each occasion they plan to host an activity. The new permits will be valid for at least one year, and MDAR will have the option to renew these grants, which ultimately aim to promote what the text of the bill refers to as the “long-term productivity of the agricultural resource and the sustainability of the farm enterprise.”

When Sholan entered the real estate market in 1999, developers drafted a plan to convert the farm’s 167 acres into houses. Instead, the city of Leominster was able to buy the land with the help of an APR. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)

When Sholan entered the real estate market in 1999, developers drafted a plan to convert the farm’s 167 acres into houses. Instead, the city of Leominster was able to buy the land with the help of an APR. (Rebeca Pereira for CommonWealth Beacon)In the eyes of Jared Freedman, Comerford’s chief of staff, the next step for Massachusetts is to recruit support for farmland preservation beyond the marbled halls of the State House, creating financial incentives for municipalities to prioritize preserving farmland.

This model already exists through the PILOT, or payment in lieu of taxes, program, which helps cities and towns recover some of the revenue they lose from state- or nonprofit-owned lands, institutions, renewable energy installations, and more. Land owned by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, for example, is property tax-exempt, and therefore returns no tax revenue for local communities.

In return for hosting state-owned lands, 297 communities receive aid through the PILOT program.

Freedman suggested it could be expanded to aid the state’s efforts to work with cities and towns to prevent farmland loss.

“These municipalities are struggling to pay for their schools, to pay for their fire, to pay for their EMS, to repave their roads,” Freedman said. “If you're gonna try to protect forests and farmlands, the municipalities can't suffer.”

In the state with one of the highest rates of farmland conversion, the stakes have never been higher.

Rebeca Pereira is an engagement editor and agriculture reporter at the Concord Monitor.

This article first appeared on CommonWealth Beacon and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: "https://commonwealthbeacon.org/environment/betting-on-the-farm/", urlref: window.location.href }); } }