Image

“In view of the Circumstances surrounding his disappearance, it is felt he should be declared administratively dead.” United States Army Air Corps

5 September 1945

There seems no end to the categories of America’s war dead. Enlisted dead, North African dead, kindred dead, new dead, dead friend, dead officer, Bunker Hill dead, ethnic dead. And it goes on and on.

We rage against war as a corrupt pretext to spawn new hierarchies of the dead. And many of us find the goodness in the lives of our dead obscured by all the horror and all the wasted blood.

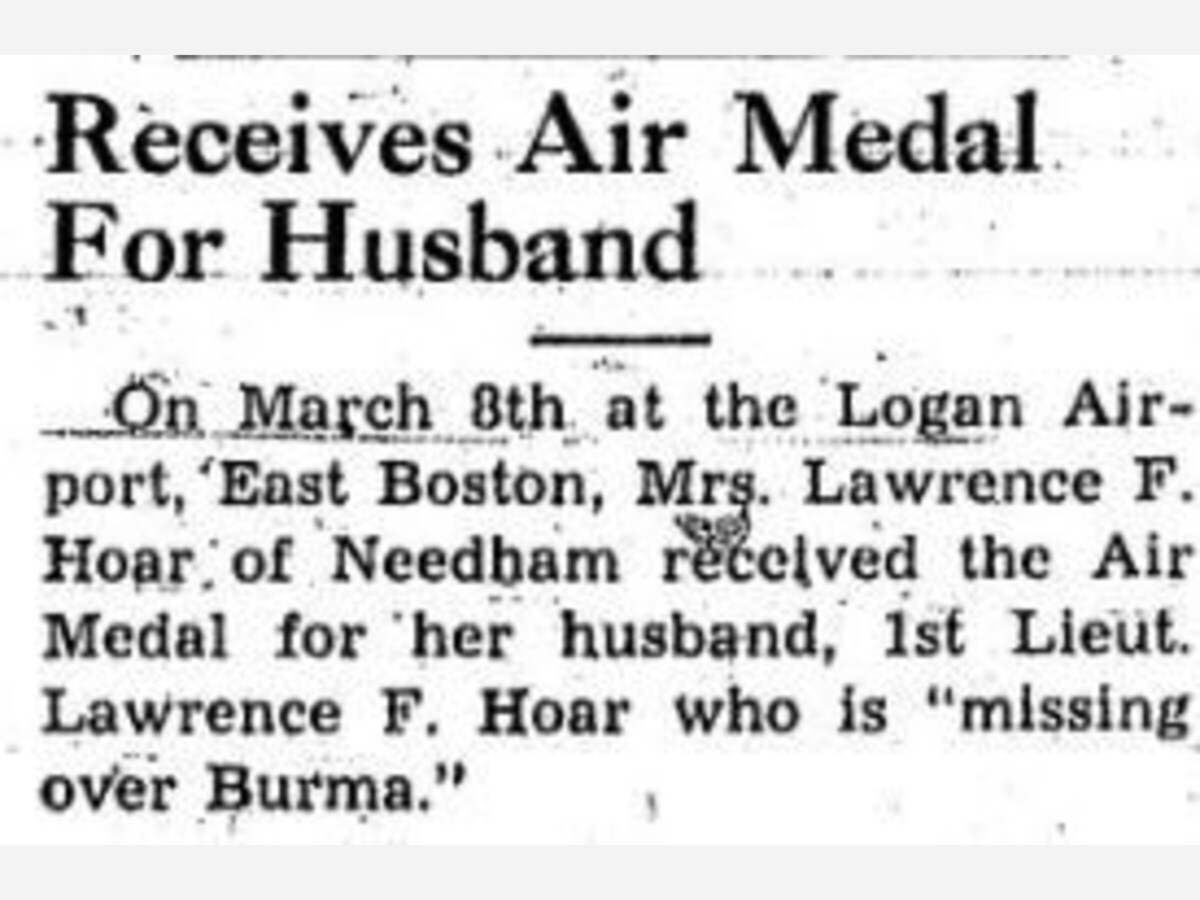

First Lieutenant Lawrence F. Hoar, a Norfolk resident, flew search and rescue missions over Burma for the United States Army Air Corps in World War 2. Under monsoon conditions, Lieutenant Hoar departed Schingbwiyang, Burma at 13:30 hours on May 7, 1944.

When I think of the dead, I also think of the could be dead, about 160 men I knew in Fort Gordon, Georgia in 1965. There we went through basic infantry training together, I, as a national guardsman, they as enlistees and draftees.

For 95 percent of them, the word future meant Vietnam, graveyard of the newer dead. And because you knew you would go back home while they went over there, you felt smug and sheepish at the same time.

Within hours after the 21-year-old Lt. Hoar was overdue, members of his squadron searched for him.

During that winter of 1965, we marched hundreds of miles, we wrestled each other in hand-to-hand combat in the Georgia red clay, and low-crawled 100 yards through craters and barbed wire always staying beneath what our drill sergeants told us was live machine gun fire. Back in camp, on many nights we went to the PX. We sat at a table near the juke box and listened to “Mr. Lonely” while we talked about home.

The Air Corps said no humans lived where Larry Hoar probably went down, and the jungle growth would cover his plane within a few days.

By the time you made it through basic training, you also had made friends and formed memories. Today you might call it bonding, whereas back then you would say you served with someone.

I sometimes wonder if any of those I served with ended with their names on the Vietnam Wall. Denney, Gaines, Jackie Billington? How many wake at night in a soldier’s grave, turn to the nearby dead, and say “I knew they’d get me?”

In addition to his wife Marjorie, Larry left his mother Catherine, two brothers Ralph and Tom Hoar, and three sisters, Mary Lavasseur, Mildred Bonifazi, and Rosemarie Hoar.

After the could be dead—or before, for dead follows no order—come the hometown dead. And my hometown of Franklin has too many. At the northern end of the town common stand several monuments, each inscribed with the names of the hometown dead.

It’s 81 years now, and Larry Hoar’s mother, brothers and sisters have all passed on. In his memory, His sister Mary flew the American Flag each day. His sister Mildred named one of her daughters—my wife Lauren—after Larry.

Thus, each Memorial Day is a day to set aside politics, and is a time to recall with reverence the lives of friends and kin, white and black, natural born and naturalized and every other American military dead.

--Paul DeBaggis

Paul DeBaggis has held many elected and appointed offices in Franklin. He is a retired building official. He writes in magazines and local newspapers.

[Editor's Note: The bridge over the railroad tracks near Norfolk Center bears the name of Lawrence Hoar]