Image

The life story of Franklin-born Albert Deane Richardson reads like a novel and seems the stuff of Hollywood. In little, more than 30 years of life, Richardson managed multiple careers, adventured across the landscape of the Civil War and was murdered in New York City by a jealous man. Even the trial of his murderer had fantastical elements.

Finally freed from Salisbury prison camp, Richardson and his companions were fortunate to have a Union sympathizer within earshot of the place. He had arranged hiding places for the trio beneath the hay in the loft of his barn in a location hard to detect should soldiers come searching. But, with a staunchly Confederate wife, none suspected. And Rebel horsemen and patrols went off by every road searching for the escapees.

They were less sure that they could stay hidden from numbers of black and white children that considered the hayloft their preserve and spent much time rough housing there. Nor could they count on anything but water from their helper – his wife was master of the household foodstuffs and would miss even a crust of bread – and perhaps suspect something.

Eventually, after a few days, as the Confederate patrols began to give up their search, their helpmate led them on an escape path and linked them with a new escapee, a New Hampshire man who had gotten himself into a Confederate uniform and simply walked out of the camp. With his “disguise and detailed instructions on how they might find their way north – and survive the cold – they were on their way.

Time after time, when they were exhausted, near starvation, or in danger of detection, local slaves risked all to bring them food, and send them to safety where they might rest a bit. They also found and identified potential friends among the white southerners through secret signs of ‘The Sons of America’ – an informal group that appears to have arisen for that specific purpose. And they found safe houses and even small settlements largely composed of Union supporters that they reached in time for a modest Christmas celebration.

As they journeyed on, it was the same story. Local slaves helped them, as did Confederate deserters, and whole families of Southerners or “border” people unwilling to fight for the Confederacy. These latter folks regularly sent their men and boys to hide in the forests rather than risk being drafted into service by Confederate patrols – a practice they called lying out. One middle-aged mother said her son had not slept under her roof in two years and slept always with a rifle in hand, determined to kill or be killed if the “Home Guard” – the Rebel interior troops – ever found him.

Further into Tennessee they were fortunate to run in with Dan Ellis, a famous guide for those seeking escape from the South. He was reputed to have safely brought some 4,000 people to the north in innumerable individual trips.

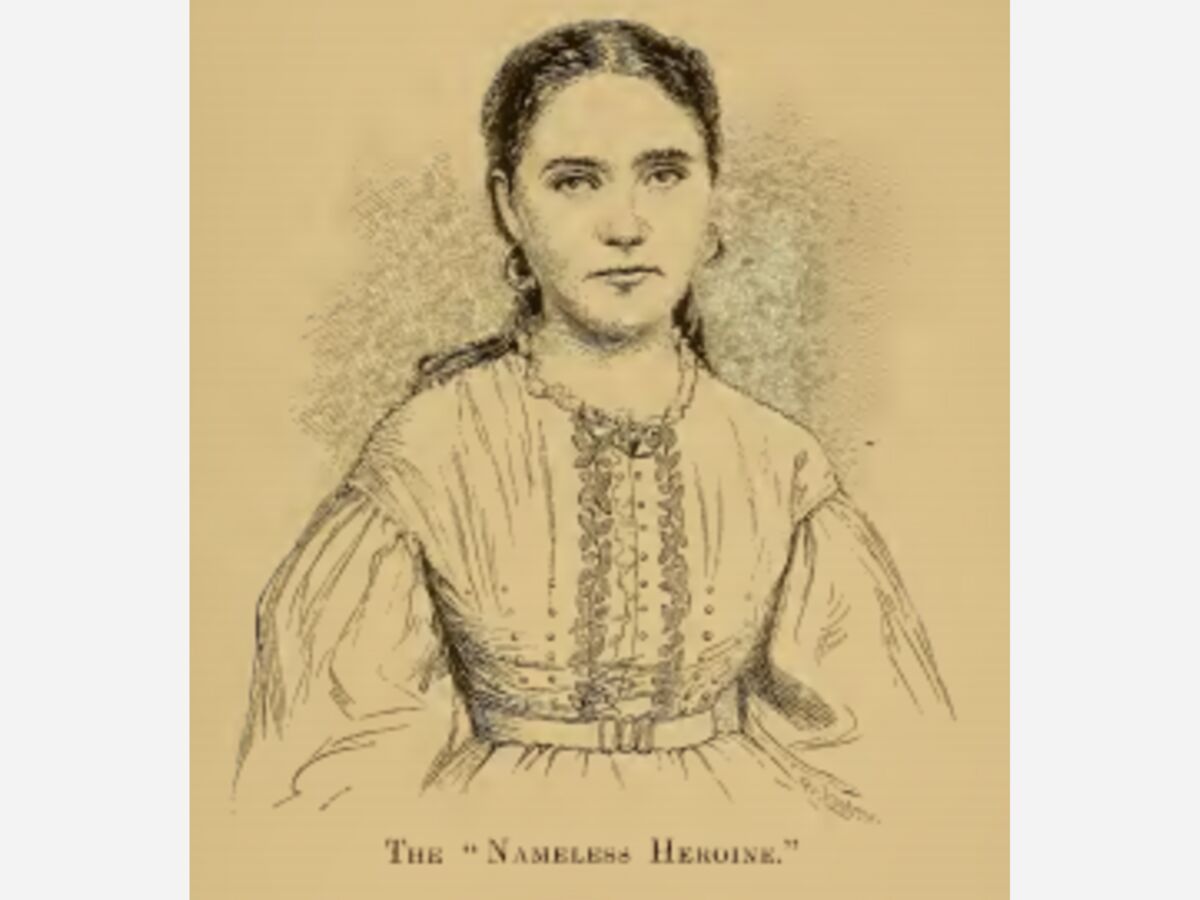

As they got closer to safety, Richardson and a few others managed to obtain the use of horses. But the danger suddenly increased, as local Unionist let them know a band of hundreds of Rebel guerillas was in the nearby hills. The group broke into two parties. one group on horse taking advantages of speed and the other on foot traveling by stealth. Richardson followed his guide that in the dark he supposed to be Dan Ellis for several miles before realizing the lead horseman was a horsewoman, whom he dubbed the “Nameless Heroine.” As they crossed a bridge to safer territory, she cantered ahead to verify that “the coast is clear” and then returned alone to her home many miles away.

Still they were in disputed territory. and each encounter with another soul was still a drama of revealed or concealed loyalties. Food and shelter became paramount concerns leading to risk taking – but finally, on January 13, 1865, they reached Knoxville, where the Stars and Stripes flew openly. They were free. And still in possession of their 'precious cargo' -- the names of the Union dead from Salisbury.

[After the war, Richardson revealed the nameless horsewoman to be a Miss. Melvina Stevens.]

to be continued