Image

Colin Young|SHNS

With the number of people in the state's shelter system way up, and the amount of money the state spends to support homeless programs also surging, Massachusetts reached the limits of the resources it had available to solve the problem of homelessness.

We're not talking about this week. That was more than 30 years ago.

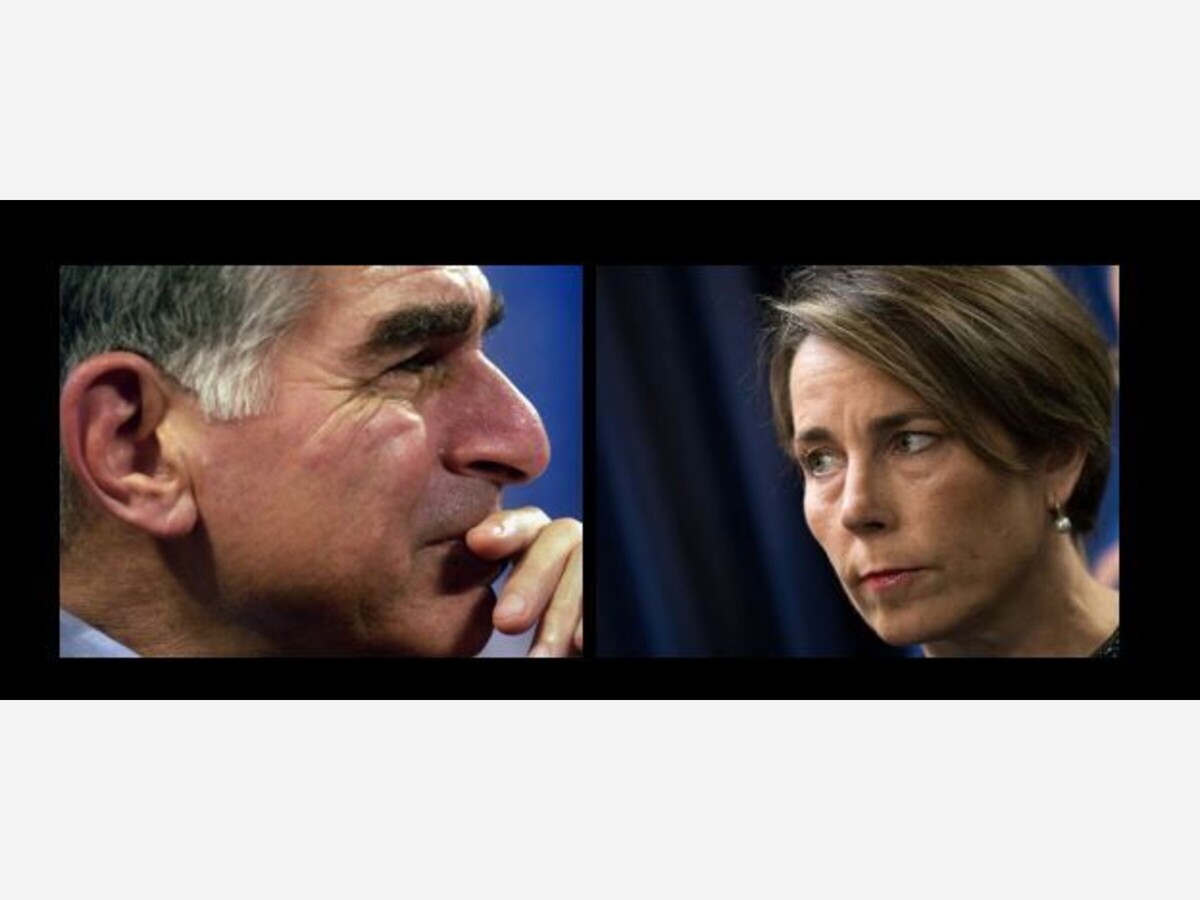

Yes, Gov. Maura Healey this week won the blessing of a friendly judge to impose a cap and waitlist for emergency shelter services in part out of concerns that the recent influx of new shelter seekers will require the state to rapidly spend down the hundreds of millions of dollars the Legislature has devoted to the program.

But this week's headlines were really just the latest chapter in a story that Massachusetts has been writing for parts of five decades.

Nancy Kaufman wrote some 31 years ago about "The Massachusetts Experience" of state government's response to homelessness from 1983 to 1990, and warned then that future policymakers would have to wrestle with difficult decisions about the extent of the Bay State's commitment to truly stamping out homelessness and providing for the necessities of all.

"In Massachusetts, a working model for solving the problem was created, but basic questions remain: Do we, as a commonwealth, want to solve the problem, and at what cost? Has too much been devoted to emergency responses and not enough to prevention? Can we build permanent housing fast enough and affordable enough for the poorest citizens to benefit? Are we willing to guarantee a job to anyone who wants one despite age, ethnicity, or disabilities? and, What role does government have in finding solutions to the problem?" she asked in an article published in the New England Journal of Public Policy in 1992. "These are the questions with which we as a commonwealth now struggle. The answers are not simple. One thing is certain: the problem of homelessness is expensive to solve, particularly if one considers the thousands of men, women, and children affected each year."

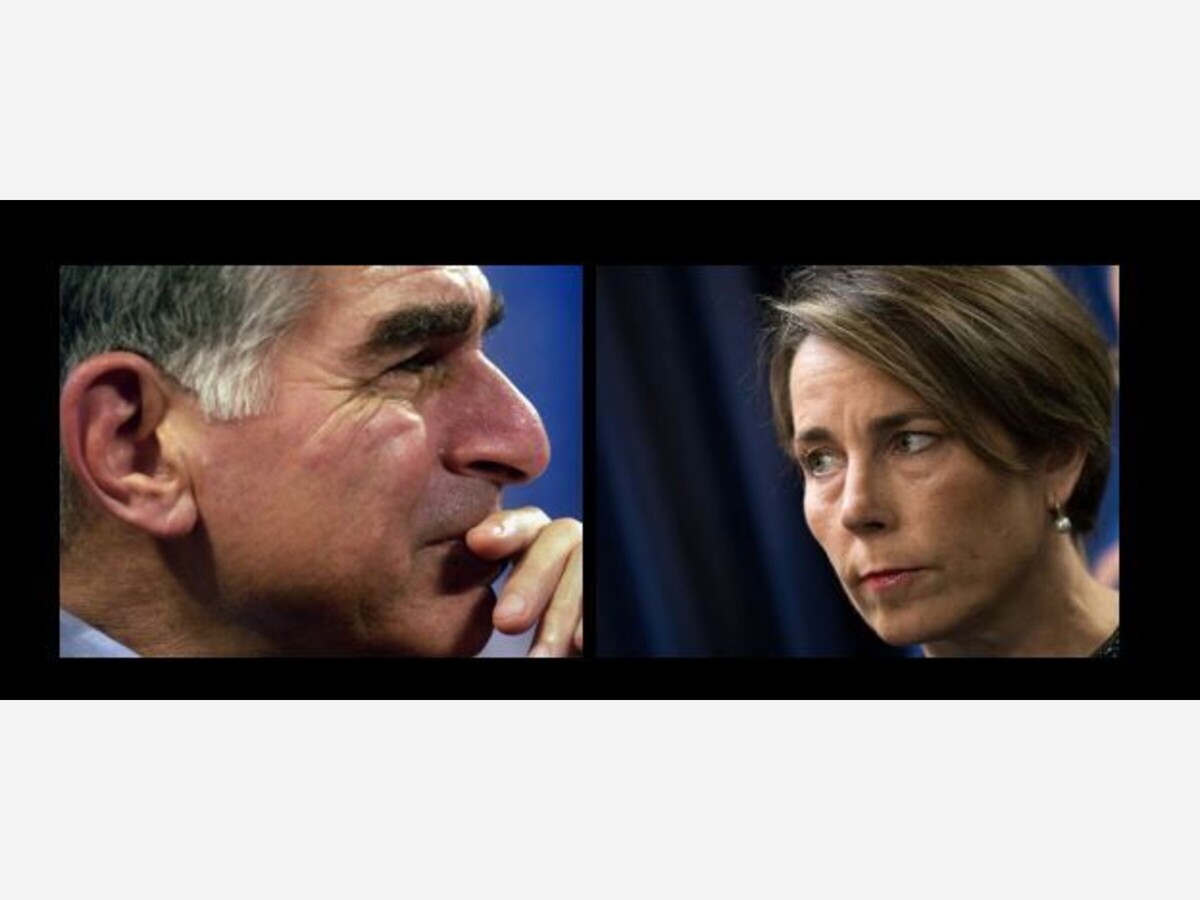

Kaufman knew what she was writing about: she had a strong hand in the state's efforts to address homelessness in the 1980s as deputy director of Gov. Michael Dukakis' Office of Human Resources, assistant secretary of human services, and deputy commissioner of the Department of Public Welfare. She became executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston in 1990. She later worked as CEO of the National Council of Jewish Women.

Dukakis -- who turned 90 on Friday -- announced in his 1983 inaugural address that Massachusetts would embark on a major effort to assist the homeless -- he said he'd hold an emergency Cabinet meeting to "begin immediately to put together a statewide effort which will provide the necessities of life to those in desperate need." That year the Legislature and Dukakis put on the books the state's right-to-shelter law, which calls for the state to provide shelter to families or pregnant women in need.

"If needed, we will draw on surplus state hospitals, unused public schools, and as a last resort, National Guard armories to shelter the homeless and to distribute surplus food," the governor said.

At that point, just two state-funded shelters were operating. By 1990, the number was more than 100 shelters, with 70 for families with children. The state budget for homeless programs increased from $10 million in fiscal year 1983 to more than $200 million in fiscal year 1989, Kaufman said. For the emergency assistance program alone, the state budget commitment began at $2 million in 1983 and expanded to $8.3 million in 1987.

And Kaufman even gave voice to the same frustrations that municipal leaders are airing now, telling the Local Government Advisory Council in October 1987 that the Dukakis administration understood that its efforts to deal with homelessness put a burden on communities that hosted shelters or motels used as shelters.

"We've taken families off the streets but created problems for those communities (that shelter them) because of schooling," Kaufman said, the News Service reported at the time. The LGAC heard at the same meeting about Dukakis' plan to provide extra local aid money for cities and towns educating students temporarily residing in local shelters or hotels.

Republican Gov. William Weld took office in 1991 promising to control state spending and clean up Massachusetts' mess of a budget as a recession set in following the "Massachusetts Miracle." Kaufman wrote in 1992 that she was concerned that more safety net programs would be dismantled as the number of people entering the shelter system increases, "resulting in far greater fiscal costs for the commonwealth of Massachusetts, not to mention the human costs."

Kaufman concluded: "It would be tragic if the infrastructure built over eight years of careful planning and program development was torn apart in an effort to balance the state budget. The short-term fiscal gains may look significant, but the long-term costs would be very serious. In the final analysis, if we, as the richest nation in the world, cannot guarantee a decent home for every citizen, who will?"

When Dukakis went all in on dealing with homelessness in 1983, he said that Massachusetts had "thousands of homeless [who] wander our streets without permanent shelter, and we must provide it." Forty years later, Gov. Healey last month declared that "the fact of the matter is we have reached our limit" with both physical capacity to house people and the personnel to serve emergency assistance beneficiaries.

"I think the important point here is that Massachusetts has done its job and so many have come together to make that possible," Healey said, suggesting some finality to her decision to cap the state's guarantee of shelter for families and pregnant women.

House and Senate Democrats in 2023 are content to let Healey manage the shelter crisis as she sees fit. The first-year Democrat governor has taken hardly any flak from other elected officials on Beacon Hill as she has moved to limit the state's largesse.

Rep. Marjorie Decker of Cambridge, who grew up in public housing and has said her life experiences gave her a "master's in poverty," was a lonely elected voice calling on the administration to stop its planned changes to the shelter system this week. She told the News Service she found the court decision to clear the way for Healey's cap "disappointing."

"It doesn't solve the problem. We can go ahead and say we're not eliminating the [right-to-shelter] law, but we are eliminating the law," Decker, who co-chairs the Public Health Committee, said. "At the end of the day, we've got children who are going to have nowhere to sleep."

Decker added, "What I want to know more about, quite honestly, from the governor's office, I don't need the semantics about whether or not you're limiting the law or not. What I need to know is: really, what's the plan?"

The plan as outlined this week by the Healey administration includes offering mobile vouchers to 1,200 families that have been in the emergency assistance system for longer than 18 months and partnering with the feds for a work authorization clinic this month to get migrants on track for employment. Both efforts are aimed at opening up space for families newly entering the system.

But once the number of families seeking emergency assistance shelter hits Healey's limit of 7,500, which is expected to happen imminently, the state will begin shifting applicants to a waitlist. It becomes less clear where families will spend the night. A triage system will assess where families land on the list, with four levels of priority laid out in Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities guidance.

Once a spot becomes available, officials plan to contact a families by email, phone call and text using information they provided. They will have until 12 p.m. the following business day to accept an offer for shelter placement.

"These are hard calls. I just want to acknowledge that with the public, nobody wants for this situation, and I think all of us have been working together inside and outside the government to really deal with what is a heartbreaking situation," Healey said Thursday.