Image

By James C. Johnston Jr.

I have a very good friend who moved from Franklin a very long time ago. He is a very well educated gentleman, has a beautiful wife, and successful children. He is a proud grandfather, and he loves gossip! He is an unabashed digger into the doings of others and snickers at this foible as a guilty pleasure. I myself must confess to a small flaw in my own character in-so-much that I too enjoy gossip, but in a moment of inspiration, I said to my friend, “We are not gossips. We are ‘Social Historians’! Now that makes what we like to do very respectable."

Let’s face it. Most historians are indeed gossips on a grand level, but as historians, all of our efforts to know the past, at an intimate level, are justified by our “Scholarship”. Well that’s my story, and I am sticking to it. That is why I have always enjoyed history as a vast learning experience in which we look into the doings of thousands of generation past, and by the way, you get to read other people’s mail.

Now let’s face it. Some people want their mail read. Take Julius Caesar for example, his reports sent back from Gaul reporting on his great triumphs in the First Century B.C.E. made him a hero back home in Rome and set him up to be the first de facto emperor of the Roman Empire. Everybody who could read Caesar’s mail which was published as De Bello Gallia, or, Concerning the Gallic Wars. Caesar, ever a modest man much like myself, was forced by circumstances to admit what a brave heroic genius he was.

In the course of becoming a rather advanced stamp collector over the last seventy-five years, I have acquired a huge number of items known a “Postal History.” Postal History is quite simply covers, that is stamps or ratings and post-marks used on their original envelopes. I have letters from the great and famous, as well as, from every-day people whose lives are also part of the human drama. Almost all postcards, which are used, carry personal messages, are great human historic documents, and the personal nature of some of these messages are amazing for their revelation of great intimacy.

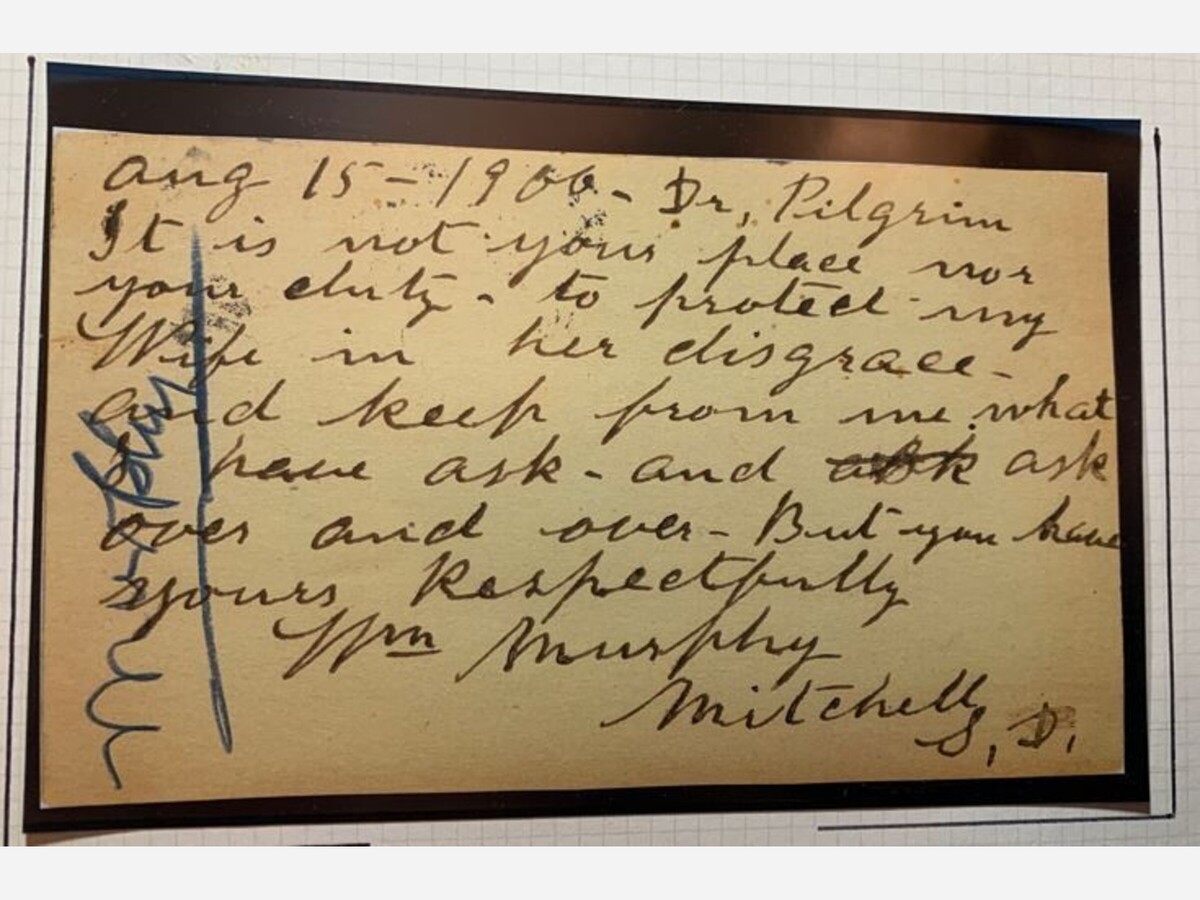

For example, I have in my possession a postcard [pictured above], which I bought from an old-time dealer in an accumulation of early mail, which hints at a very interesting and sad story. It was addressed to a Doctor Pilgrim living in Poughkeepsie, New York. It reads as follows,

August 15, 1900-Dr. Pilgrim, It is not your place-nor your duty-to protect my Wife in her disgrace and keep from me from what I have ask-and ask over and over-But you have. yours Respectfully Wm.Murphy Mitchell, S.D.

Obviously there is a very interesting story involving a complex human drama here in frontier America in South Dakota which had seen wars with the Native Americans, and gold rushes, and land rushes, and massacres within the previous twenty years. Now, here was the sociological pheromone of a little social upheaval revealed on a “Penny-Post Card” for all to see. I think that by sending this very public missive, Mr. William Murphy had shown himself to be a brutish bully of violent inclinations. Dr. Pilgrim was, no doubt, a good fellow who saw this poor woman’s plight and rescued her from a very bad domestic situation.

The question now comes, Is Dr. Pilgrim a hero or an interfering busy-body? Isn’t social history grand? Now let us go back to 1844 and a letter sent from the Canterbury, New Hampshire Post Office serving the Shaker Community in that town. Before we go on with this bit of postal history, we should know that the Shakers were a religious people who shook in anticipation of the second coming of Christ. Their worship involved dancing in lines of men and women, facing each other, eventually reaching a state of ecstasy in anticipation of The Lord’s appearance someday.

The Shakers led a simple and segregated life, men and women living apart, in a state of celibacy. The congregations of Shakers expanded by means of conversion and supported themselves in their villages by dealing in seeds, making house-hold objects such as brushes and brooms, also brewing medicines, and making furniture which is still highly prized by collectors today. The Shakers first came to America from England under the leadership of Mother Lee in the 1770’s and eventually spread out in the Eastern part of the United States in about three dozen villages ranging from New Hampshire in the North, to Ohio in the West, and Kentucky in the South. My mother, Clara Johnston was a friend of the very last Shakers during the last years that they lived. They shared an interest in folk art and exchanged many letters.

The Shakers were very charitable. They were an agrarian people who took in orphans, the sick, and the needy. When those taken in as orphans reached their majority, they were given the choice of remaining in the Shaker Community or going out into the world. If they chose to go out into the world, they were given the means to buy a farm or to set up in trade. If they chose to stay in the Shaker Community they were expected to obey the Shaker rules and embrace the celibate life.

When I saw this stampless cover, which I now hold in my hand, sent from the Shaker’s Canterbury Post Office, I quickly bought it from the stamp dealer for a few dollars along with some other pre-postage-stamp covers for five dollars each. All of the covers were great buys, but this one would be a great bit of social history. The letter, addressed to Mr. Abiel Cogwell in Canterbury, N.H., reads as follows,

Sept. 2d, 1844 Dear Sir, It is painful to me to write you that your son is dangerously sick. The doctor has but little hopes of his recovery. He is not sensible more than a moment at a time [and] has his discharges as he lays in bed. We have had two physicians here to see him. He was worse last night and remains so today. I feel very anxious to have him here. Yours respectfully, Mrs. Ruby Stone

I surmise that the stricken boy might have suffered a falling-out with his family in Canterbury and been thrown-out on his own resources by his father. Having no way to live or support himself, he became very ill, and only the Shakers were willing to take him in. Did the boy die? Did his family come to collect him? Was he nursed back to health? Alas, I have no further letters about the matter. Reading other people’s mail may sometimes be frustrating, never-the-less it is all social history a great part of collecting stamps. Worry not. There are many more letters to follow.