Image

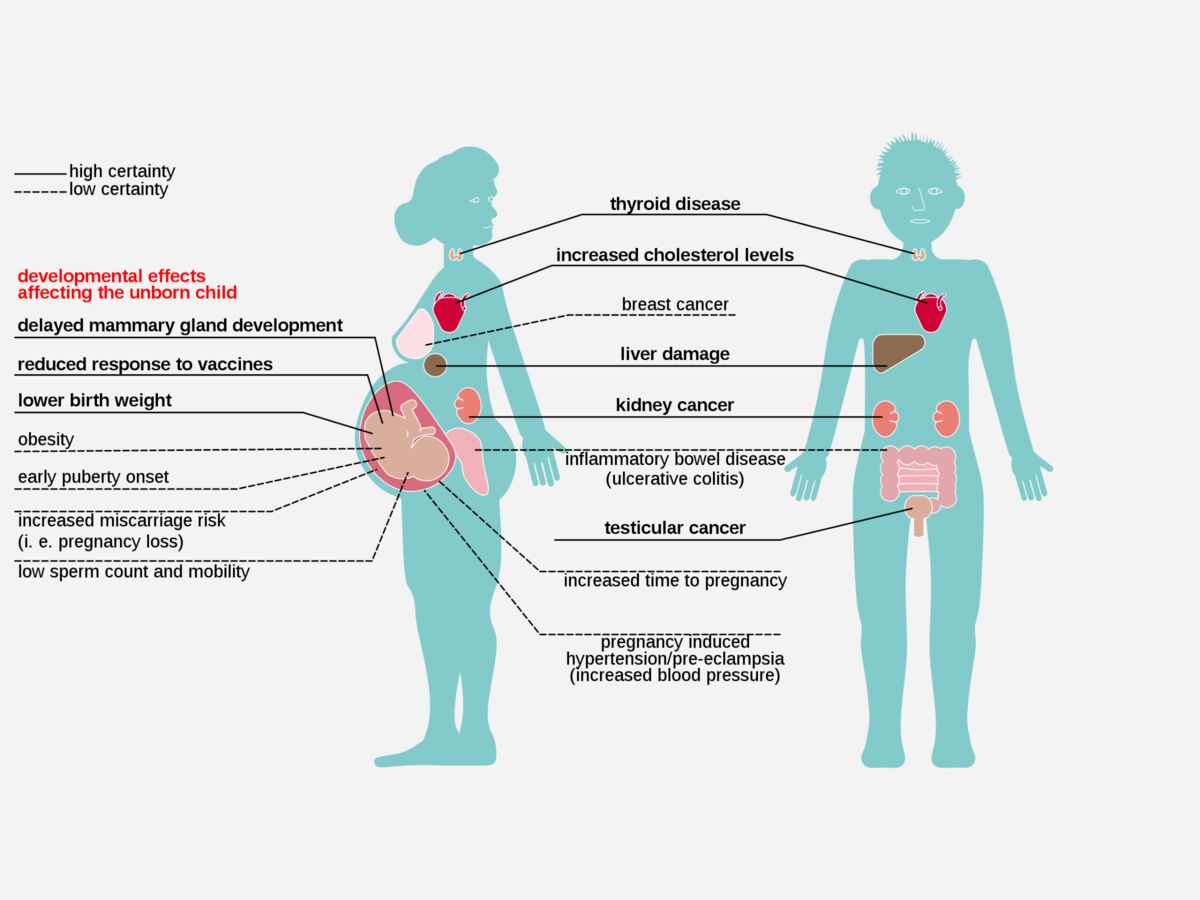

PFAS chemicals are in the news a lot lately. The acronym can refer to either per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or perfluorinated alkylated substances. All are synthetic organofluorine chemical compounds that have multiple fluorine atoms attached to an alkyl chain. But for most of us, it is enough to know that they are often called simply “forever chemicals” because they can persist in the environment and in living tissue, essentially forever. (See image above, Effects of exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) on human health, used courtesy of the European Environmental Agency)

The exact dangers posed by PFAS chemicals are just now starting to be understood but governments have been moving quickly to identify, control, and eliminate them. One of the better know sources of PFAS chemicals is firefighting substances (for example the “foam” used to put out aircraft fires).

Fortunately, according to the Franklin Fire Department, efforts to completely reduce or eliminate PFAS material in their operations are well under way.

According to a statement issued by Fire Chief James McLaughlin, a discussion in the Franklin DPW 2020 Drinking Water Report mentioned the topic of PFAS pollution. It was explained that one of the possible sources of PFAS groundwater contamination was the use of “legacy” firefighting foams, which routinely contained 2% - 5% PFAS by volume; specifically, Class B AFFF, which is used to extinguish burning hydrocarbons or flammable liquids.

McLaughlin said the department wants to make sure the public is aware that the Department has been working to address this for some time. In 2018, in consultation with the Massachusetts Department of Fire Services, MassDEP chose to implement a foam “take-back” program to assist fire departments in removing these foams from current stockpiles and ensuring they are properly disposed of, rather than used during trainings or firefighting and subsequently released into the environment. MassDEP’s program targeted foams manufactured before 2003, as manufacturers stopped production of `suspect’ foams in 2002.

Recognizing the challenges proper disposal would present to the budgets of most municipalities, according to McLaughlin, MassDEP decided to fund the disposal of these legacy foams through its Massachusetts Chapter 21E / Bureau of Waste Site Cleanup (BWSC) capital funding, consistent with programmatic goals of “pollution prevention” and elimination of “threats of release” of hazardous materials. Under the “take-back program,” MassDEP offered to pay for foam removal and disposal; the local fire departments were responsible for replacing the foam with safer foam alternatives.

As part of this take-back program, Franklin Fire was able to dispose of approximately fifty (50) gallons of outdated foam, at no expense to the townspeople.

McLaughlin went on to explain that more modern products still use PFAS chemicals but at a lower level than legacy foam. In addition, PFAS products in use are more stable (so-called “short chain”) and expected to have less of an impact on the environment. New “Fluorine Free Foam,” aka “F3” foam, is just now entering the main-stream market. Currently, the majority of Franklin Fire apparatus, that carry foam, carry these newer F3 foams, he said.