Image

Auditor Diana DiZoglio took her legislative audit fight to court Tuesday, asking a single justice to break a legal logjam that she says has dragged on for more than a year.

As Massachusetts barrels into an election year, the dispute over whether lawmakers must open their books under a voter-approved audit law is poised to stay front and center — shaping races and arguments about accountability up and down the ballot.

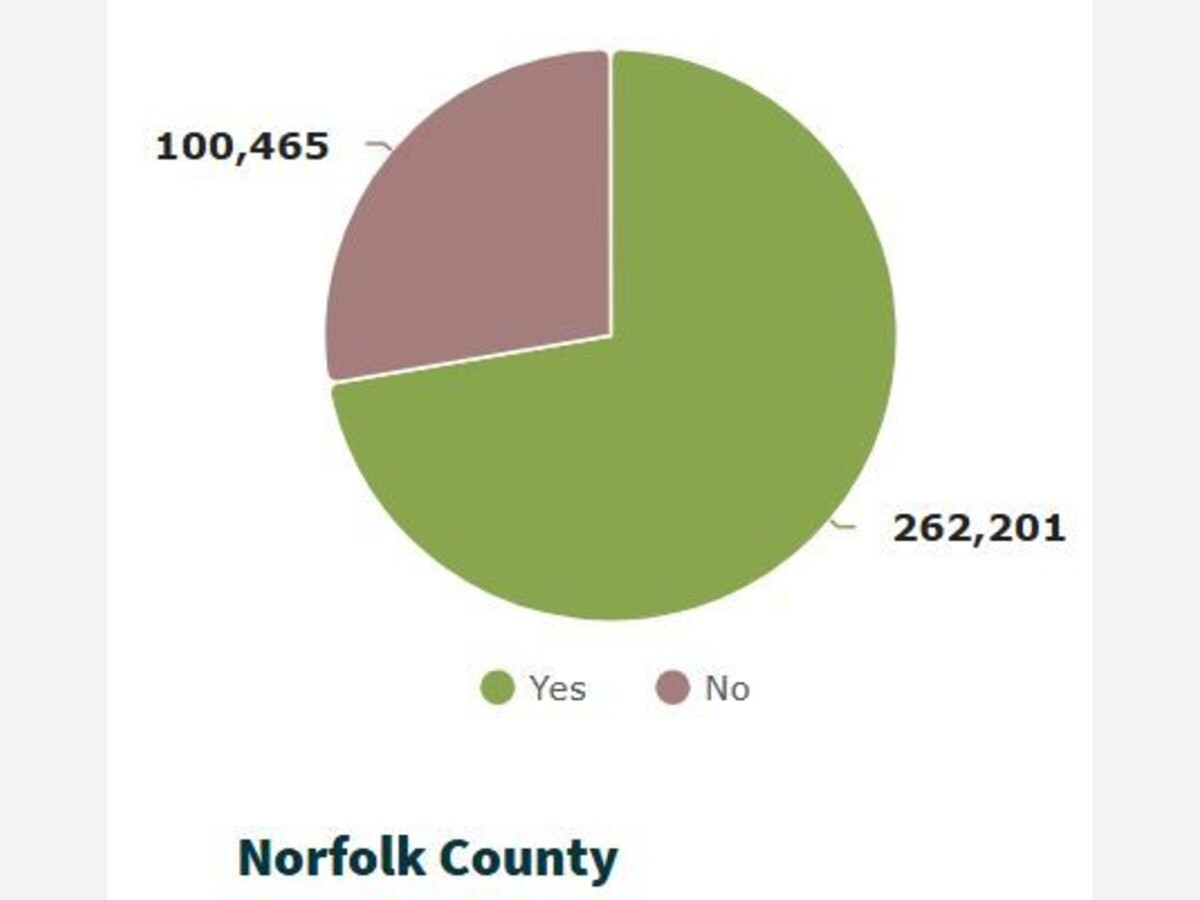

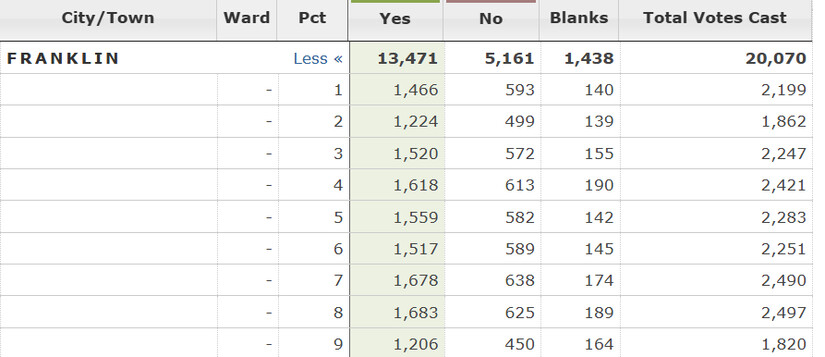

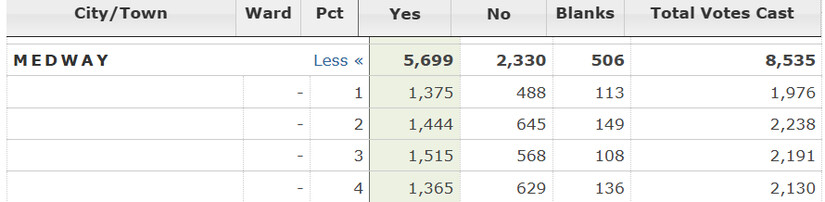

Voters in the state overwhelmingly supported the ballot question [Question 1 on the 2024 ballot] supporting an audit, and according to polls, continued to do so. Election results for Norfolk County as a whole, are summarized above, and for Franklin and Medway, below:

At the core of DiZoglio's new lawsuit isn't just a demand that House and Senate leaders turn over records. It's a procedural plea: permission to hire her own legal muscle through the appointment of a special assistant attorney general, or SAAG, as the attorney general has not relented to DiZoglio's calls to represent her office.

The petition, filed with a single justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, lays out two intertwined requests. First, DiZoglio asks the court to authorize the appointment of a SAAG so her office can be represented in court. Second, she asks the court to directly compel legislative leaders to comply with document requests under the 2024 ballot law. At a press conference, DiZoglio emphasized the former, framing the case as a fight to even get through the courthouse door.

"We are trying to pursue litigation at no cost to the taxpayer," DiZoglio said, arguing that her office has spent months trying to line up outside counsel only to be blocked by ethics concerns raised by Attorney General Andrea Campbell.

Under state law, the attorney general typically represents state agencies. When conflicts arise, however, there is a statutory mechanism for courts to appoint special assistant attorneys general. That's the pathway DiZoglio says she's now pursuing after what she described as prolonged inaction by the AG's office.

"There is a mechanism within the statute that allows for state agencies to go to court to get the appointment of a SAAG," said Michael Leung-Tat, DiZoglio's general counsel. Court involvement is necessary because the attorney general's "inaction, or sort of stalling this process" has left the auditor without representation, he said.

The ethical tangle that led here is central to the case.

DiZoglio said her office explored using outside attorneys willing to take on the litigation without billing the state — including offers from high-profile labor attorney Shannon Liss-Riordan and others — in an effort to avoid taxpayer costs. She also acknowledged that Michael Minogue, a former medical device executive who has since launched a Republican campaign for governor, offered to cover the cost of outside counsel so taxpayers would not have to pay, an arrangement that drew heightened scrutiny given his political ambitions. Those efforts ran into resistance from critics who questioned whether counsel privately funded by a gubernatorial candidate could represent a state office.

According to DiZoglio, the auditor's office sought guidance from the State Ethics Commission to resolve that issue. The commission advised that outside attorneys could litigate against the Legislature only if they were formally appointed as special assistant attorneys general — a step that requires approval through the courts.

"That's why it's actually taken so long," DiZoglio said, describing a roughly 60-day process to obtain ethics guidance. She said her office has not accepted any outside payments and is seeking court approval to ensure any arrangement is lawful.

Leung-Tat said the broader request — asking the court to enforce the audit law itself — is the next step from the SAAG question. "It's all connected," he said.

Asked about the potential cost to taxpayers, DiZoglio said the filing itself relies on existing staff and does not add new expenses. She added that her office is seeking a SAAG "who is not going to charge the office."

The lawsuit also crystallizes what DiZoglio describes as an almost total breakdown in communication with legislative leadership. Asked when she last spoke with House Speaker Ronald Mariano or Senate President Karen Spilka about the audit, DiZoglio said it was likely years ago, before she became auditor.

"I don't know that the Senate president actually spoke to me about this ever when I was in the Senate. Besides in passing seeing folks, I haven't had the opportunity to talk to these people in several years," she said, adding that she would welcome a public forum or moderated discussion. Private, behind-the-scenes meetings with House speaker staff, she said, have been offered.

At the press conference in her office, DiZoglio was flanked only by two members of her legal team. There were no other constitutional officers at her side, no lawmakers in attendance — a familiar tableau in a building where she has faced stiff institutional resistance, even as she points to broad support outside the State House.

Senate President Karen Spilka's office referred the News Service to Sen. Cindy Friedman's office when asked about the lawsuit. Friedman chairs a Senate subcommittee created to respond to the 2024 audit law.

Friedman said the Senate "has tried to work with the Auditor and her office to understand what she is seeking to audit beyond the independent, professional audits that the Senate already undergoes each year."

"Since January 2025, the Senate subcommittee has attempted to engage with her directly, and invited her to testify before the subcommittee, which she declined. To date, the information the Auditor has provided the Senate regarding what she is seeking has been vague at best, much like the questions she has left unanswered when asked for specific information regarding the scope of the audit by the Attorney General. Given that, and that an independent, professional audit is done annually, we must assume that the Auditor’s intentions are purely political," Friedman said. She concludes that "at a time when constitutional norms are being challenged nationally, we cannot allow them to be undermined here in Massachusetts."

The fight is unfolding against a charged political backdrop. DiZoglio acknowledged that candidates in multiple races are seizing on the audit issue, including Republicans running statewide. She bristled at suggestions that pressing the case could hurt Democrats, saying she's been urged by some in her party to dial it back.

"It is not the pursuit of justice on behalf of the people of Massachusetts that's hurting Democrats," she said, arguing that transparency and accountability resonate across party lines. She reaffirmed her Democratic affiliation while expressing disappointment in party leaders' handling of the dispute.

The court could reject her requests. Asked what happens if that occurs, DiZoglio offered a shrug and a note of uncertainty. "This is my first rodeo," she said. "So we'll see what happens."

For now, the lawsuit means that the legislative audit battle — once confined to letters and press statements — is before the judiciary, where questions of ethics, authority and separation of powers could be tested just as voters tune in for another election season.

Campbell's office did not return a request for comment. Mariano declined to comment.

Sam Drysdale is a reporter for State House News Service and State Affairs Pro Massachusetts.