Image

The life story of Franklin-born Albert Deane Richardson reads like a novel and seems the stuff of Hollywood. In little, more than 30 years of life, Richardson managed multiple careers, adventured across the landscape of the Civil War and was murdered in New York City by a jealous man. Even the trial of his murderer had fantastical elements.

After the attempt on his life, Albert Dean Richardson and the woman he hoped to marry, Abby Sage McFarland resumed their respective lives, or tried to. On March 31, 1867, Richardson wrote with passion, hope, and a lot of realism to Abby, then staying with family in Massachusetts, only a fortnight since being shot by her husband.

“Partly from my own rashness, partly from things neither of us could control, you and I are in a little boat on a high and perilous sea. If I had any sense, you would not have been there. But I believe devoutly in the proverb that a man who isn’t a fool part of the time is one all of the time. It was foolish, imprudent, cruel to let you be on such a craft with me, when patience could have avoided it. But I loved you and took no counsel of reason.”

Discovering that McFarland had bullied his way into the rooming house where she had been staying, stealing or destroying her correspondence, the manuscripts she had been long working on, and every other kind of personal thing, Abby decided to keep her distance, staying in Massachusetts with her two children. And, as she later explained, suffering McFarland to have made contact with every friend and most of her relatives to defame her character, ending with a characteristic vow that she and Richardson would never marry.

McFarland then attempted to regain custody of the children through the Massachusetts courts but seemed thwarted when Richardson asked his friend, former Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew, to provide her legal representation. But when Andrew suddenly died, the case was thrown into disarray and under duress, Abby agreed that one of her sons could go with McFarland – a compromise she soon regretted.

Rather than put her son in school as promised, McFarland, always short of money, dragged him from one lodging to another. Finally, she realized the Indiana option was the only hope. There, grounds for divorce included drunkenness, extreme cruelty, and failure to support a wife. So, in the summer of 1868 she moved to Indiana to establish residency and file for divorce against McFarland, meaning to stay there with her son Danny for at least a year, by which time she hoped her legal appeal would have succeeded.

For his part, Richardson stayed in touch, continued working on his biography of Grant, and traveled west to Kansas and Chicago, where he was involved with plans to start a new newspaper.

McFarland meanwhile, actively slandered both of them and took court action against Richardson for “alienation of affection.”

After 16 months, while Albert was in the far West, touring the just-completed transcontinental railroad, Abby’s divorce was finally granted and on October 31st she returned to her father’s house a free woman. And Albert joined her, spending Thanksgiving in Massachusetts with her family before returning to New York. But then came the telegram.

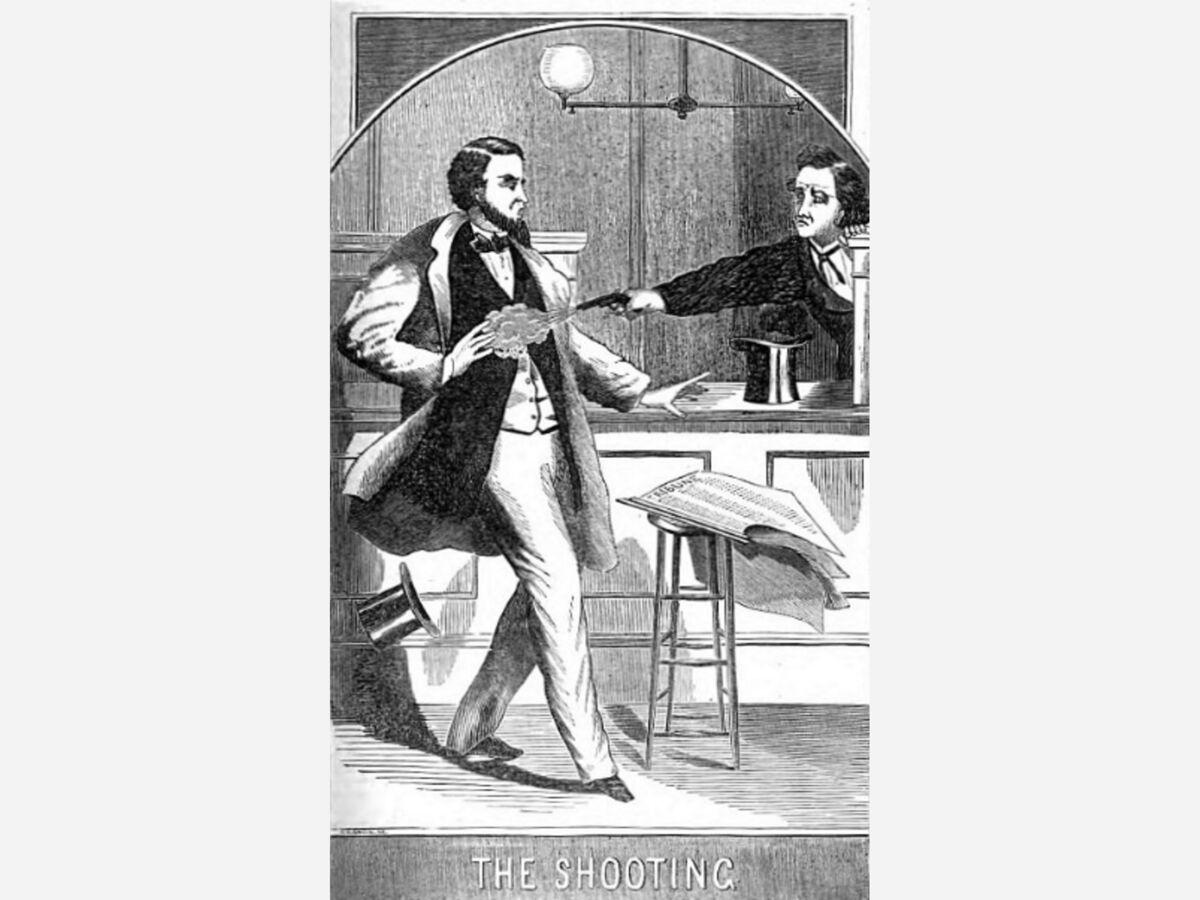

On November 25, 1869, Richardson was finally back in the offices of the Tribune in New York City when Daniel McFarland rushed in and fired a pistol at him, pointblank, in front of witness, Daniel Frohman (a future Broadway producer), mortally wounding him so that he lingered on for several days.

When the police brought McFarland to Richardson’s bedside, he rallied and pointed to him as his assailant.

Arriving from Massachusetts to comfort him, Abby and Albert decided that regardless of the imminence of the latter’s death, they would be married.

And so they were, by none other than the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, then one of the most esteemed religious figures in the United States. [His sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe was famed as the author of the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin]. On November 30, at 5:30 pm the brief ceremony was completed and Mr. and Mrs. Albert Deane Richardson, in the style of the times, became a reality.

But widow’s weeds followed quickly, as Albert finally succumbed in the pre-dawn hours of Dec. 2.

In a letter to his wartime comrade, Junius, a few months after McFarland’s first attack, Richardson had written, “I [had] decided not to arm myself because I did not want the blood of any man and particularly of this most wretched man, on my hands. I have the same feeling still...So, if he attacks me again, I shall mean to run a very great risk rather than do deadly harm to him.”

And, so, that promise had been fulfilled.

The press, other than the Tribune, had a field day with the murder and the death-bed marriage, ramping up and amplifying the most extreme of McFarland’s claims and making of the widow a harlot and apostle of free love in the eyes of the public.

But Richardson’s many friends at least mounted a large funeral in the city, which was followed by a more modest but even more heartfelt event in Franklin, where Richardson’s body achieved its final resting place at the City Mills Cemetery.

To the horror of many, after a sensational eight-week trial, McFarland was acquitted of murder on May 10, 1870 on the grounds of insanity.

To be continued.